The Royal Navy’s colossal intelligence failure concerning the presence of German Zeppelins at the Battle of Jutland, and its long-term effects on the U.S. Navy.

By Bruce McWhirk, January 7, 2022

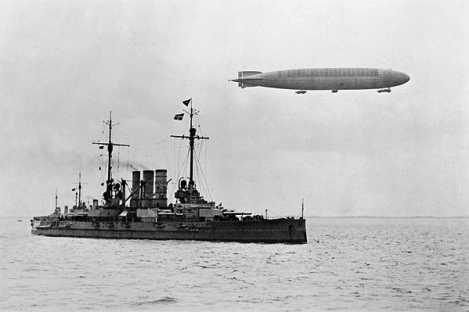

“EYES OF THE GERMAN FLEET”: Super-Zeppelin L.31 and the German battleship SMS Ostfrieland. This photo was taken shortly after L.31’s first flight 12 July 1916. (photo: navalhistory.com)

The Imperial German Navy deployed numerous scouting Zeppelins over the waters of the North Sea during World War 1, but during the Battle of Jutland (31 May-1 June 1916) no Zeppelin sighted the British Grand Fleet. One Zeppelin, L-11, was sent out and it found the British Grand Fleet, but just after the epic sea battle had ended. Nonetheless, after the battle, the prevailing view in the British Admiralty (and among all Allied fleet commanders) was that during the battle Zeppelins had played a vital role in saving the German High Seas Fleet from imminent destruction.

Just prior to the start of Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916, and during the battle itself, up to five German naval Zeppelins were sent out to locate the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet. Largely due to poor visibility and strong northeast winds, none of the German airships made contact with either fleet during the main battle. The Zeppelins were recalled in the late afternoon on 1 June 1916. The following day, in the early morning hours, Zeppelins were sent out again from the German Naval Air Base at Nordholz in Lower Saxony. Under the dim dawn light, Zeppelin L.11 finally located the main British force. By then, the battle was over. But the sighting of this lone Zeppelin at that early morning hour, combined with the total chaos and losses of the previous night fight, and the heavy loss of three British battlecruisers the previous day, unnerved the Royal Navy commander of the Grand Fleet. By then, Admiral Jellicoe declined to pursue neither the out-of-range High Seas Fleet nor its heavily damaged German Navy ships, like the once-vaunted, but now pulverized German battle cruiser SMS Seyditz, that slowly lumbered back to port.

In reality, Zeppelins had played no role in the Battle of Jutland– the largest sea battle in world history up to that time.

After the battle, however, high ranking Royal Navy officers at the Admiralty strongly believed otherwise. They concluded that Zeppelins were to blame for the Royal Navy’s severe losses and a major reason for the Grand Fleet’s “Pyrrhic victory. ”Their belief was likely based on a dispatch received by the Admiralty from Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, Commander-in-Chief, Grand Fleet, on 31 May, 1916 (the first day of battle,) that reported actions in the North Sea, to the westward of the Jutland Bank, off the coast of Denmark.

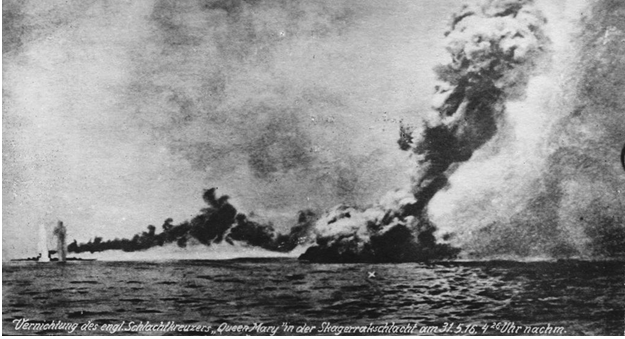

Opening Salvoes at Jutland: Battle Cruiser H.M.S. Queen Mary explodes. (public domain)

Early in the battle, on 31 May 1916, at 4:26 pm., the British battlecruiser H.M.S. Queen Mary exploded after having been hit by massive gunfire from two German battlecruisers: SMS Seydlitz and SMS Derflinger. 1,266 British sailors lost their lives; eighteen survivors were picked up by the destroyers H.M.S. Laurel, H.M.S. Petard, and H.M.S. Tipperary and the German Navy warships.

Within minutes after this catastrophe, Admiral Jellicoe, Commander of the Grand Fleet, (although then still unaware of the H.M.S. Queen Mary’s destruction) sent another dispatch to the Admiralty. It read:

“Possibly Zeppelins were present also. At 5.50 p.m. British cruisers were sighted on the port bow, and at 5.56 p.m. the leading battleships of the Battle Fleet, bearing north 5 miles. I thereupon altered course to east and proceeded at utmost speed. This brought the range of the enemy down to 12,000 yards. I made a report to you that the enemy battlecruisers bore south-east. At this time only three of the enemy battle-cruisers were visible, closely followed by battleships of the ‘Koenig’ class.”

Hours later, after receiving and reading this dispatch, Royal Navy officers at the Admiralty formed the opinion that the scouting Zeppelins had sighted the Grand Fleet early in the battle, and that this early intelligence had been relayed by the Zeppelins to Admiral Reinhard Scheer, who in turn ordered the German High Seas fleet to retreat to safety, and reposition itself, by concentrating the battle fleet and destroyers along a rear-ward line for a killing strike on the Grand Fleet. According to this opinion, this last decisive maneuver had saved the entire High Seas Fleet from imminent destruction.

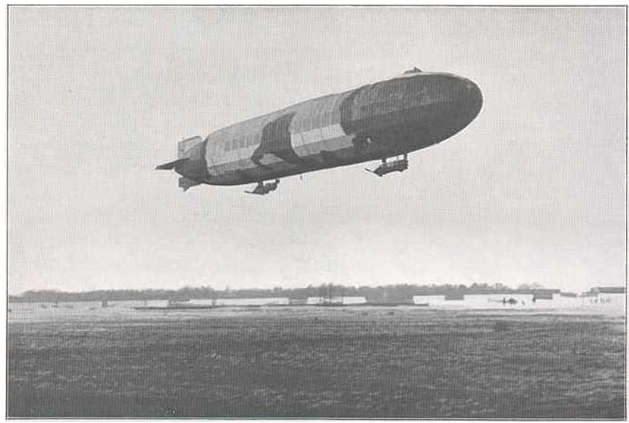

In fact, German Navy Zeppelins never sighted the Grand Fleet during in the Battle of Jutland. The German Navy Zeppelin L.11 (shown above) finally located the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet on June 2, 1916, the morning after the battle had ended. In the photo above Zeppelin L.11 appears covered by “Frisian Camouflage” while departing on a reconnaissance mission over the North Sea. (photo: public domain)

In his book, The Grand Fleet, 1914-1916, Admiral Jellicoe acknowledged that a single Zeppelin had been sighted and engaged by twelve British ships in the early morning hours of the day following the battle. He wrote:

“Our position must have been known to the enemy, as of 2:50 a.m. the fleet engaged a Zeppelin for quite five minutes, during which time she had ample opportunity to note and subsequently report the course and position of the British fleet.” (p.484)

“The presence of the Zeppelin at 3:30 a.m. made it certain our position at the time would be known to the enemy… at 3:38 Rear Admiral Trevelyan Napier, commanding the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron, reported that he was engaging a Zeppelin in the position to the westward of the Battle Fleet. At 3:50 a.m. a Zeppelin was in sight from the Battle Fleet, but nothing else, … she disappeared to the eastward. She was sighted subsequently at intervals…” (pp. 383-384)

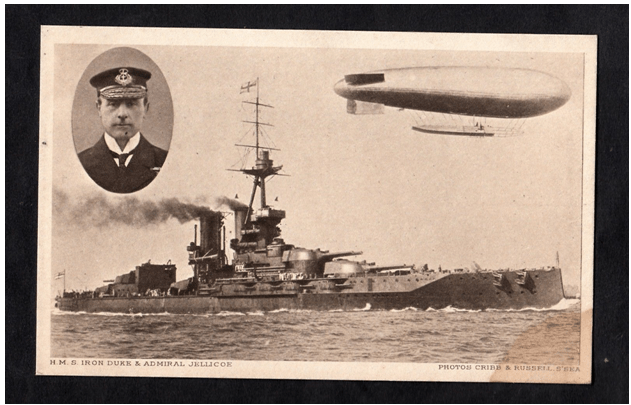

Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and his flagship H.M.S. Iron Duke at sea with Royal Navy Sea Scout blimp flying overhead, 1916. (contemporary postcard)

Admiral Jellicoe further noted:

“What are the facts? We know as the sun rose the High Seas Fleet (except such portions as were escaping via the Skaw) were close to the Horn Reef, steaming as fast as the damaged ships could go for home behind the shelter of German mine fields. And the Grand Fleet was waiting for them to appear and searching the waters to the westward and northward of the Horn Reef for the enemy vessels; it maintained the search during the forenoon on June 1st, and the airship, far from sighting the Fleet late in the morning, as stated, did so, first at 3:30 a.m., and on several occasions subsequently during the forenoon. And if that airship reported only twelve ships present, what an opportunity for the victorious High Seas Fleet to annihilate them! One is forced to the conclusion that this victorious fleet did not consider itself capable of engaging only twelve British battleships.” (p. 410)

Only three days after The Battle of Jutland had ended, high-ranking officers in the Admiralty still held firmly to their belief that scouting Zeppelins had sighted the Grand Fleet early in the battle, and this sighting was the main reason why the High Seas Fleet had escaped destruction. This belief apparently caused someone in the Admiralty to leak this story to the London press. On June 4, 1916, the tone of the British press about the Battle of Jutland suddenly changed from shock, horror and grief to outright anger, frustration and fury when The Weekly Dispatch in London expressed the following opinion:

“THE LESSON OF IT ALL

Why did we fail? Why were the Germans able so to dispose their forces as to be able to attack when our battle-cruisers were unsupported, and to retire comparatively unscathed when the 15-inch guns came up? The answer is one word – Zeppelins.”

The Admiralty prepared a secret report on the Battle of Jutland that was published on 20 September 1917. This report contained an analysis on the role Zeppelins had played during the battle. It gave Zeppelins full credit for saving the German fleet from destruction, and, it asked this haunting question: “If the situation at Skagerrak had been reversed, if airships had enabled us to discover the whereabouts of the North Sea Fleet and destroy it – who can deny the far-reaching effect this would have had upon the outcome of the war?” In this report Royal Navy officers theorized that if at the Battle of Jutland, the High Seas Fleet had been decisively defeated, Germany would have been forced to surrender and to seek peace with Britain and the Allies. According to this interpretation, World War I should have ended in 1916 after a dramatic victory at Jutland by the Royal Navy with the staggering destruction of German High Seas Fleet.

Heavily damaged in the battle, SMS Seydlitz was hit by twenty-one main caliber shells, several secondary caliber shells and one torpedo. 98 men were killed and 55 injured (public domain)

In his memoir published in 1919, the year after the war ended, former First Sea Lord Admiral Jacky Fisher still fulminated about the outcome of the Battle of Jutland. He wrote:“We know, now, how very near – within almost a few minutes of total destruction (at the time the battle-cruiser “Blucher” was sunk) – was the loss to the Germans of several even more powerful ships than the “Blucher,” more particularly the “Seydlitz. Alas! There was a fatal doubt that prevented the continuance of the onslaught, and it was indeed too grievous that we missed by so little by so great a “Might Have Been! ” Well, anyhow we won the war and it is all over.”

At the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, however, a former German naval officer who had commanded Zeppelins during the war refuted the British version of the battle. He told a member of the Allied Naval Commission in German Waters that during the Battle of Jutland, no scouting Zeppelins ever had sighted the British Grand Fleet. If that had been the case, the German Naval officer asserted, the German fleet certainly would have avoided the battle.

Nonetheless, Royal Navy officers at the Admiralty persisted in their belief that Zeppelins had played a decisive role in the Battle of Jutland by providing critical aerial reconnaissance that allowed the German High Seas Fleet to slip away undetected and escape total destruction. In holding onto this view, they convinced key naval officers around the world, and especially in the United States, of the importance of using rigid airships for aerial reconnaissance in fleet operations.

Testifying in 1919 before the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, Captain T.T. Craven, U.S.N., then commander of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer), said, “It is said, and we believe that the German Fleet was saved through the agency of her aircraft at the Battle of Jutland. That fleet was in probably the most precarious position that any inferior fleet ever found itself, but it got away, and I believe it was through the agency of the German aircraft. Admiral Jellicoe stated in his book that, in his opinion, a dirigible was worth two light cruisers. You must remember the peculiar conditions obtaining in these waters. The visibility was poor. If aircraft were vulnerable there, how much more valuable must they be under atmospheric conditions where there is good visibility, such as we have in the West Indies and in the Pacific?” (p. 70)

Captain William A. Moffett, U.S.N. was appointed commander of the Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) in 1921. He shared the British opinion that Zeppelins had played an indispensable role as aerial scouts that had protected and even saved the German High Seas Fleet from imminent destruction during this epic sea battle. Admiral Moffett had read the Admiralty’s secret report on the Battle of Jutland. As a consequence, he was convinced, like so many others were, that in the post-war period, that the U.S. Navy required Zeppelins – large rigid airships – in order to conduct essential long-range aerial reconnaissance missions to protect the U.S. fleet, especially across the expanse of the Pacific.

In 1926, Rear Admiral Moffett doubled down on his view that Zeppelins, as scouts, had allowed the German High Seas Fleet’s to escape destruction at the Battle of Jutland.

During Admiral Moffett’s testimony before the Naval Affairs Committee of the House of Representatives the following conversation took place:

“Admiral MOFFETT. … I can best show in a broad way what the German rigid airships accomplished in the war by quoting from a secret British report under date of September 20, 1917: ‘From the results already given of instances, it will be seen how justified is the confidence felt by the German Navy in its airships when used in their proper sphere as the eyes of the fleet. It is no small achievement for their Zeppelins to have saved the high sea fleet at the battle of Jutland, to have saved their cruiser squadron on the Yarmouth raid, and to have been instrumental in sinking the Nottingham and Falmouth. Had the positions been re- versed in the Jutland battle, and had we had rigids to enable us to locate and annihilate the German High Sea Fleet, can anyone deny the far-reaching effects it would have had in ending the war?

“… Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, of the British Navy, in a letter to Admiral Sims, in 1919, wrote, ‘I have a firm belief in the value of Zeppelins for naval purposes. They have become somewhat discredited during the war because the Germans put them to the wrong use by bombing instead of scouting. I can not see that a heavier-than-air machine can ever be so efficient a scout as the Zeppelin, because she can never get the same radius of action. The Zeppelin is bound to give better information than the aeroplane, as she can hover and observe closely whilst hovering. Had the Germans had their Zeppelins out on May 31, 1916, the battle fleet would never have gained contact with the high sea fleet. They would have turned as on August 19th,1916…”

Mr. BRITTEN (interposing). Those two stories, one from Jellicoe and one from somebody else, would lead one to believe that the Germans Zeppelins did take part in the Battle of Jutland, while Jellicoe said they did not.

“Admiral MOFFETT. I am not sure about the date.

“Mr. WOODRUFF. That covered a period of two days?

“Admiral MOFFETT. Yes, sir.

“Mr. WOODRUFF. As I understand the situation, the Zeppelins were of tremendous value to Germany on the second day. That enabled the high seas fleet to escape the British.

“Admiral MOFFETT. That is what I would judge from what they said.

“Mr. BRITTEN. Admiral Jellicoe referred to the Battle of Jutland, which took two days, and said they could have done better if they had had Zeppelins there.

“Admiral MOFFETT. If he had had Zeppelins.”

The U.S.S. Akron, ZR-4, the U.S. Navy’s first Zeppelin aircraft-carrier, launches scout biplanes, 1932. (photo: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command.)

Under Admiral Moffett’s leadership, as head of the Naval Bureau on Aeronautics (1921-1933), the U.S. Navy’s massive rigid airship program gained full momentum; it became the world’s foremost developer of new Zeppelin flying aircraft carriers capable of launching and retrieving scout planes to support the U.S. Navy’s fleet operations.

REFERENCES:

John Toland, The Great Dirigibles; Their Triumphs and Disasters (formerly titled: Ships of the Sky -The Story of the Great Dirigibles), Dover Publications, New York, 1972, p.52

John Arbuthnot Fisher, Memories, by Admiral of the fleet, Lord Fisher, Hodder and Stoughton, London, 1919, vol. 1, p. 49

Admiral Viscount JellicoeThe Grand Fleet, 1914-1916: Its Creation, Development and Work, George H. Doran Co., New York, 1919, pp.484, 383-384, 410

William F. Trimble, Admiral William A. Moffett, Architect of Naval Aviation, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2007

“The Lesson of It All,” The Weekly Dispatch, London, 04 Jun 1916

“No Zeppelins in Jutland Battle,” Aerial Age Weekly, New York, vol. 8, March 3, 1919 p. 1268

Naval Appropriation Bill: Hearings Before the Committee on Naval Affairs, By United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Naval Affairs U.S. government printing office, Washington D.C., 1919, Captain T.T. Craven’s testimony, p. 70

Rear Admiral William A. Moffett’s Testimony, 28 January 1926, Hearings Before Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives on Sundry Legislation Affecting the Naval Establishment, 1925-26: Sixty-ninth Congress, 1st Session, U.S. government printing office, Washington D.C., 1926, pp. 710-711