THE EXPLOITS OF AMERICAN PILOT IN WORLD WAR I –

ENSIGN NORMAN JACKSON LEARNED, U.S.N.R.-F-C.

By Bruce K. McWhirk

(photo: Elmira Star-Gazette)

Ensign Norman Jackson Learned, U.S.N.R.-F-C. was the only U.S. Navy aviator who successfully led an attack that sunk a German U-boat during World War 1

ENSIGN NORMAN “JACK” LEARNED STATIONED AT RAF BASE FOLKESTONE

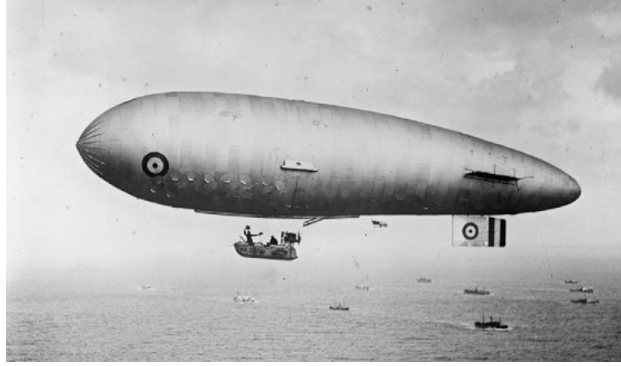

Ensign Norman “Jack” Learned was a 22 years old American Naval Officer who commanded a British airship Sea Scout Zero airship -SSZ.1. While patrol over the English Channel, he led a dramatic hunt that sank a German U-boat in September, 1918.

He was stationed at the RAF Base at Folkestone in Kent, Southern England. After the creation of the Royal Air Force in April 1918, that merged the air services of the British Army and Royal Navy, this site’s name changed from Royal Naval Airship Station (RNAS) Capel Le Ferne to RAF Base Folkestone. British nonrigid airships regularly conducted anti-submarine missions from there to points along the French coast to protect the great traffic of naval ships, troop ships, food ships and war supplies on commercial vessels in convoys in the English Channel.

The term “blimp” originated at (RNAS) Capel-Le Ferne with a remark made in December 1915 by Flight Commander A.D. Cunningham, R.N. during an inspection of a Sea Scout (SS) airship. He ran his thumb across the airship’s taut gasbag and after hearing the sound, he imitated it, saying, “Blimp!” This term caught on among the station’s amused personnel and soon “Blimp” became a universal slang term for nonrigid airship.

Ensign Learned flew a Royal Navy Sea Scout Zero (SSZ) blimp – SSZ.1, nearly identical to the one seen in this photo. (photo: Royal Navy). British hydrogen-filled blimps successfully conducted anti-submarine missions, including coastal patrol / convoy escort missions and/or mine detection missions throughout World War 1.

COMMANDING A BLIMP ON A ROUTINE ANTI-SUBMARINE PATROL MISSION

On the afternoon of September 16, 1918, the captain of the airship SSZ.1, U.S. Navy Ensign “Jack” Learned took off from the Royal Air Force (RAF) Base Folkestone to fly a routine anti-submarine patrol mission.

At a point off of Cap Griz Nez, France, he looked down and spotted an oil slick on the ocean surface. The oil slick formed a long widening line that ran directly toward England.

Suspecting the presence of a German U-Boat, Ensign Learned in SSZ.1 followed the oil slick. After flying for about a half an hour, all traces of the oil slick disappeared. At that location, about seven miles offshore from RAF Base Folkstone, he signaled by wireless radio for a fleet of nearby armed drifters to investigate. Ensign Learned dropped his airship’s two bombs, as the drifters dropped depth charges, and underwater detonations occurred about 30 minutes later. A U-boat was definitely sunk, and this event marked the first (and only) time during the entire war that a U.S. Navy aviator, an airship captain, led an attack that resulted in a confirmed sinking of a German U-boat.

A Great Yarmouth Drifter HMD Gregory Albert during World War 1 (photo: Royal Navy)

An eyewitness to the German U-boat’s sinking was Duncan McMillan, a 51-year old Scottish deckhand aboard His Majesty’s Drifter, HMD Calceolaria. Recalling the event, he said,

“The highlight of Calceolaria’s war time career came on September 16th, 1918 when drifters Calceolaria, Young, Crow, East Holme, Fertility, and Pleasants wereordered to hunt down and prosecute SSZ.1 which was on coastal patrol in the English Channel. A German U-boat was being chased down on the surface until she dived at which time the drifters having fired repeatedly on the submarine began dropping depth-charges. The airship began dropping bombs upon her last and predicted location until eventually three loud explosions occurred deep below the water’s surface and a large black oil slick announced the U-boat’s destruction and all her crew. Whatever the cause of the submarine’s final demise all vessels shared in the victory over the hated nemesis.”

(photo: The Times of London)

Calceolaria, was a 92-ton steam trawler from Inverness, owned and operated by R. Irvin & Sons Ltd of North Shields. It was a commercial drift-netter working in the North Sea. Drifters were robust boats built like trawlers to work in most weather conditions, but designed to deploy and retrieve drift nets. The little boat fished out of Kirkaldy, 27 miles southwest of Dundee, Scotland when she was requisitioned by the Royal Navy and redeployed as a minesweeper and anti-submarine patrol boat soon after World War 1 began.. The trawler was pressed into service and renamed HMD Calceolaria with the Naval Reserve, and was attached to the Royal Navy’s famous combined-arms command, “Dover Patrol.” Calceolaria carried a three-pound anti-submarine gun and depth-charges, and was posted to patrol anti-submarine nets around the approaches to Dover, off the Downes along the Kentish coast, and at the mouth of the Thames estuary.

(photo: The Times of London)

A Drifter Fleet at Sea (photo: Sir Archibald Hurd, History of the Great War – The Merchant Navy, London, 1921)

(photo: The Times of London)

A GERMAN U-BOAT IS SUNK

The German U-boat sunk was most likely UB 113 (a UB 3 type submarine) commanded by Obitlieutnant Ulrich Pilzecker, Imperial German Navy. Part of the Flandern II Flotilla, UB 113 left Zeebrugge, Belgium on September 14, 1918, and was heading for the Western Approaches to the English Channel via the northern route. UB 113 was never heard from again.

Following this lengthy northern route, German U-boats often left Zeebrugge and circumnavigated Britain, by sailing up the North Sea, rounding Scotland in the Atlantic, and going down through the Irish Sea, slipping past the Isle of Man, Ireland and Wales, to reach the waters off of Land’s End and Lizard Point, Cornwall, in order to prey upon the Great Britain’s busiest commercial shipping lanes and sink as many merchant ships as possible.

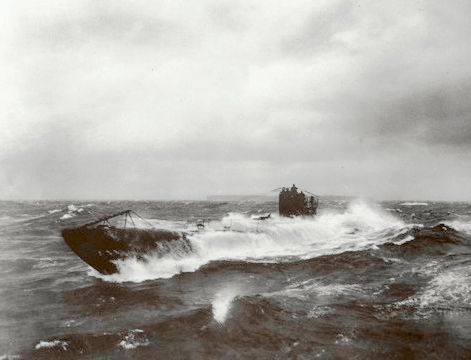

Although this photo depicts UB-148 on the open seas, German UB class submarines were designed as coastal submarines during World War 1 (photo: National Archives)

It appears that UB 113 may have deviated from its pre-determined course and had tried to take the far more dangerous but far shorter route directly through the English Channel to its ship hunting grounds. All hands – a crew of 36 sailors – were lost. Being a UB 3 type submarine, UB 113 had sunk 3 ships with a total of 4,013 tons.

IDENTIFYING THE U-BOAT SUNK IN THIS ACTION AS UB 113

Although the Official Royal Navy History claims that UB 103 was sunk by the actions of SSZ.1 and the British trawlers in the English Channel, and a number of post-war histories cite this same story, recent evidence, as identified by UBoat.net, indicate that the U-boat in question was most likely U 113. Research of German naval records and the recent discovery of a U-boat wreck off the Belgian Coast, establish that UB 103 was sunk there on August 14, 1918. Since the U-boat wreck at this site now has been conclusively identified as UB 103, that U-boat was never attacked off of Folkestone by Ensign Learned’s SSZ.1 airship and the six armed drifters.

The most likely candidate in this U-boat-sinking story is UB 113 which left Zeebrugge on September 14, 1918 for the Western Approaches of the English Channel via the north route, but never returned.

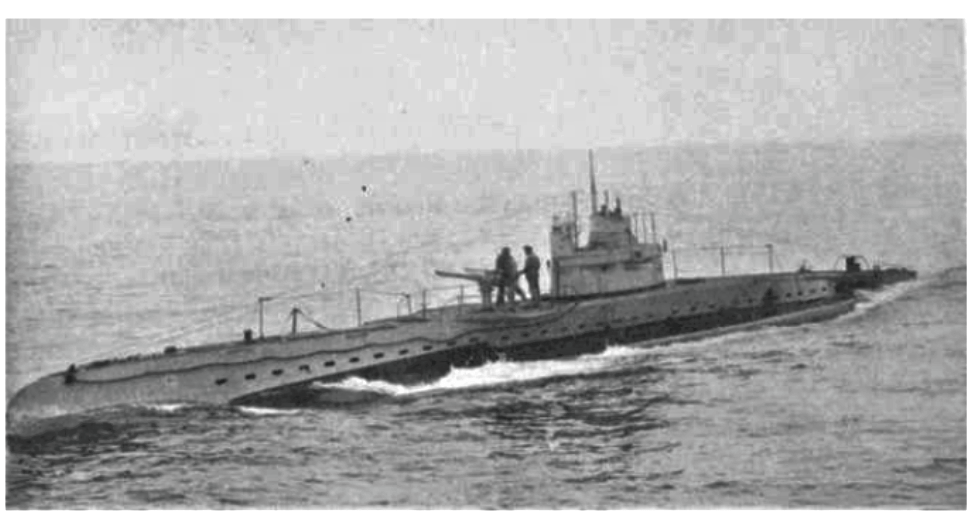

UB 40, seen in 1916, was in the same class as UB 113 (photo: submerged.co.uk)

U-Boat UB 113’s Specifications:

Year of construction: 1917

Built by Blohm & Voss at Hamburg

Displacement: 519 t / 649 t submerged,

Length: 55.3 m

Beam: 5.8 m

Draft: 3.7 m

Propulsion: 2 diesel engines, 2 electric engines, 2 propellers

Engine Power: 1,060 HP/ 788 HP

Speed: 13 kn/7.4 kn submerged

Range: 7,420 nm at 6 kn / 55 nm at 4 kn submerged,

Diving Depth: 75 m

Fuel: 68 cbm

Armaments: 4 bow torpedo tubes, 1 stern torpedo tubes, 10 torpedoes, 1 x 8.8 cm or 1 x 10.5 cm gun

Compliment: 34

A German U-Boat submerges in ocean waters during World War 1 (photo: Bundesarchiv). After being sighted, and before being attacked by Allied warships and/or aircraft, most U-boats quickly dove down below the ocean waves and usually escaped.

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ENSIGN LEARNED’S EFFORTS IN THE U-BOAT SINKING

What is the significance of Ensign Learned’s effort that led to the sinking of a German U-boat? Ensign Learned was the only American aviator to direct surface craft in the sinking of a German U-boat during the war. Even though after January 9, 1917 Germany resumed its unrestricted submarine warfare campaign in the waters surrounding the British Isles, in the North Sea, in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, sinking a U-boat was a rare occurrence.

During all of World War 1, only two German U-boats were sunk by the U.S. Navy.

In 1921, Vice Admiral Harry Shepherd Knapp, U.S.N, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, reported to the U.S. Senate Sub-Committee on Naval Affairs that during World War 1, according to all official reports, across all U.S. naval anti-submarine operations in the European theater against both German and Austrian forces, a total of twelve German U-boats were confirmed damaged or possibly seriously damaged during U.S. naval operations.

Based on Vice Admiral Knapp’s testimony, during the entire war U.S. naval forces had very few victories against German or Austrian U-boats. Only two Germans U-boats fell victim to U.S. Navy warships, most notably in the Eastern Atlantic on November 17, 1917 when destroyers U.S.S. Fanning (DD-37) and U.S.S. Nicholson (DD-52) dropped depth charges on German submarine U-58. These actions forced the U-boat to surface and its hapless German captain and crew surrendered to the Americans, while the U-boat sank.

Nonetheless, while few U-boats were sunk by the Allies, the Royal Navy, US. Navy, and French Navy fleet’s combined operations conducting coastal patrolling, convoy escort and fleet reconnaissance duties were highly effective in denying German U-boats many lucrative targets. As their combined anti-U-boat campaign gained momentum from 1917 onward, the ability of U-boats to sink Allied warships, Allied commercial vessels and neutral ships around the British Isles, in the North Sea, in the eastern Atlantic and in the Mediterranean became increasingly difficult.

Royal Navy warships and submarines and its supporting assets (mines, nets, Q-ships – combat vessels disguised as merchant ships, passenger ships, etc.) sank about 58 U-boats during the entire war (but this total is difficult to confirm.) The Royal Navy’s overall force was particularly effective in countering U-boats; it employed a wide array of available assets, including large buoys marking “war channels” along the coast, along with surface craft (Tribal-class destroyers, fast motor patrol boats, armed trawlers, yachts, etc.) and air platforms (airships, seaplanes and “Baby” Sopwith Pup bi-planes launched from small-deck surface craft.)

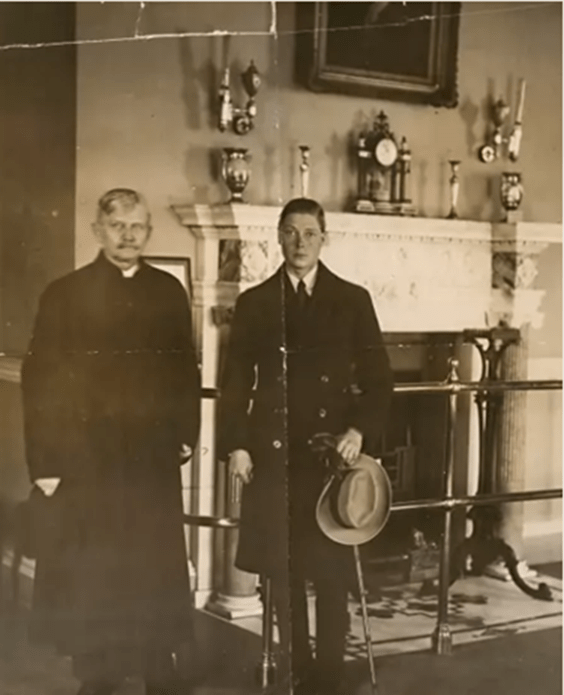

LIEUT. (j.g.) LEARNED’S RECEIVED THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CROSS FROM EDWARD, PRINCE OF WALES, NOVEMBER, 1919

For his leadership role as an airship pilot /captain of SSZ-1 in sinking the U-boat, Ensign Learned, U.S.N.R.-F-C. was awarded by King George V the Air Force Cross (AFC) in November, 1919.

At an official ceremony held in the Ballroom of the Belmont House in Washington D.C. on the morning of 13 November 1919, Edward, Prince of Wales, personally bestowed the Air Force Cross (AFC) medal on Lieut. (j.g.) Norman Jackson Learned, U.S.N.R.-F-C. and on only two other U.S. Navy airship officers for their distinguished service in aviation with the Royal Navy Airship Service / Royal Air Force.

The two other AFC recipients were Ensign Philip Jameson Barnes, U.S.N. (who set a world endurance record flying of 30 hours and 30 minutes in a Sea Scout Zero airship, SSZ.23, over RNAS Lowthorpe sub station, near Newcastle-on-Tyne city, Yorkshire, England on 29/30 May 1918) and Lieut. Commander Zachary Landsdowne, U.S.N. ( who had served as U.S. Naval Liaison Officer to the Admiralty in London during the war, and who flew in July 1919 as a U.S. naval observer on the world’s first trans-Atlantic crossing by a rigid airship, aboard the British R-34 – Lieut. Commander Landsdowne later would command the rigid airship U.S.S. Shenandoah.) Lieut. (j.g) Learned had flown with Commander Landsdowne in England during the war. The prince also decorated a large number of other American officers enlisted personnel, including former Chief Naval Officer (CNO) William S. Benson, U.S.N. (ret.) and a bevy of American nurses.

Edward, Prince of Wales, accompanied by Vice President Marshall travelled from Washington D.C. by automobile to Mount Vernon on 13 November 1919, where the prince planted a small English yew tree near George Washington’s tomb. (photo: Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

LIEUT. (j.g.) LEARNED ONLY RECEIVED A LETTER OF RECOMMENDATION FOR HIS MERITORIOUS SERVICE FROM THE U.S. NAVY

Ensign Learned hoped that he might be awarded a Navy Cross for his leadership role in sinking the German U-boat. However, during the war under Secretary of the Navy Josephus “Joe” Daniels, the U.S. Navy’s official policy was that U.S. naval personnel who performed valiant service aboard foreign ships or aircraft were ineligible to receive a U.S. Navy medal or commendation. Even though Admiral William S. Sims, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, had recommended Ensign Learned for a navy medal – a Navy Cross – for his leadership role in sinking the German U-boat, he never received any kind of U.S. navy medal for this action. Since at the time of his heroic action he was serving aboard a Royal Air Force (RAF) airship, SSZ.1, the young naval airship pilot received from the U.S. Navy only a letter of recommendation for meritorious service. He never received a Navy Cross.

“CUP O’ JOE” DANIELS – Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels signs papers (photo: Air Service Journal)

(As a side note: The common American slang “Cup o’ Joe” referring to a cup of coffee originated with U.S. sailors or “Gobs” to show their disdain and even contempt for Secretary Daniels’ official policy that forbid alcohol consumption among the ranks aboard ship.)

LIEUT. (j.G.) NORMAN J. LEARNED’S U.S. NAVY CAREER

Norman Jackson Learned was born on April 8, 1896 in the small rural American town of Alba, Pennsylvania (in 1918, this community had a population of about 148). As a teen-ager, he and his family moved to Elmira, New York. He graduated from Elmira High School in 1914. He was determined to serve his country so he enrolled in the War and Navy School, Washington D.C. After a course of training there, he took examinations for both the Army and the Navy. He was accepted by the Navy on August 20, 1917 after having passed its examination with high standing. On that date he was ordered to report for duty as a student at the “Boston Tech School,” otherwise known as Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T., Cambridge, Massachusetts.)

On the same day he graduated from the U.S. Navy’s ground school (signal training) at M.I.T., (October 30, 1917), Second-Class Seaman (Aviation) Learned volunteered to go to England to train with the Royal Navy. He subsequently was chosen as one of only 14 U.S. Navy Flying Corps cadets who were sent to RNAS Cranwell in Lincolnshire to train at its school for dirigible pilots.

RAF Base Folkestone located in Kent, southern England, not far from “the White Cliffs of Dover,” 1927. (photo: Kent History Forum – Historic England.) This aerial view shows the Silver Queen Shed, constructed in May, 1915 when the site was commissioned as Royal Naval Airship Station (RNAS) Capel-Le-Ferne. The shed was located near the cliff-walk, 147 feet above the English Channel.

Upon his graduation from RNAS Cranwell, as a certified dirigible pilot, he was commissioned as a U.S. Navy Ensign, United States Naval Reserve – Flying Corps (U.S.N.R.-F-C.)

Ensign Learned’s next assignment was to transfer to RAF Base Folkestone, part of “Dover Patrol”, arguably the world’s first combined-arms (sea-air-land) operation, set up by the Royal Navy to establish sea control over the English Channel.

Following the U-boat sinking, Ensign Learned’s supervising officer, Flight Commander Roger Coke, RAF, son of the Earl of Leicester, recommended him for the Royal Air Force Cross (AFC.)

Ensign Learned’s Sea Scout Zero airship SSZ.1 control car (photo Royal Navy)

SSZ.1’s control car was the first Sea Scout Zero (SSZ) airship control car ever built. It was designed and made by naval officers and ratings in a shed at Royal Naval Airship Station (RNAS) Capel-Le-Ferne. This new type of control car provided maximum comfort and freedom of observation over a wide swath of ocean; it accommodated a crew of three – a navigator-wireless communications officer, a pilot/commanding officer and a ratings engineer.

After the First World War ended, in February 1919 Lieut. (j.g.) Learned was assigned to temporary duty at the Naval Aviation Detachment (Lighter-than-Air) in Akron Ohio. From his experience flying and piloting Royal Navy airships during the war, Lieut. Learned was an expert on blimp design and construction. Accordingly, he was detailed to the Goodyear factory in Akron, where he oversaw the production of the U.S. Navy’s new C-class type blimps.

Lieut. (j.g.) Learned returned home on a short furlough to Elmira, New York in April 1919. He refrained from publicly discussing his exploits in the U-boat sinking with the press or anyone except for his family and closest friends. When asked by the Elmira Star-Gazette about his wartime feat, he said simply that “he did not care to state for what service he had received the cross.”

By July 1919 Lieut. Learned was flying American-made blimps and was assigned as second-in-command at the Naval Air Station (NAS) Cape May, at the southern tip of New Jersey. In the months prior to his arrival, the station had been a flurry of activity. The station was strategically significant and situated along the Atlantic coast, a few hundred miles in between both Philadelphia and New York, on a narrow peninsula and barrier beach, next to the mouth of the Delaware Bay. At the time, NAS Cape May, with Lieut. Commander Robert R. Paunack commanding, possessed the largest hangar in the United States – the newly built “Great Airship Hanger.” This massive structure was intended to house the British-made Zeppelin-type rigid airship, purchased by the U.S. Navy, R-38 / ZR-2. (This hanger never served that purpose since this large rigid airship tragically broke apart and crashed during its final flight trials over Hull England in September, 1921.) During 1919 the hanger served as the temporary home to a variety of foreign-built dirigibles purchased by the U.S. Navy during the war. The British SSZ.23 was there, as was the Italian O-1, and the French Zodiac Destroyer (ZD-US-1.)

The latest American-made blimps, the Navy’s new C-class type blimps, also were stationed and tested at Cape May. C-3 set a world endurance flight record on January 30-31, 1919 staying aloft for 27 hours and cruising the equivalent of 1,000 miles over the station; this same blimp flew in an air parade over Washington D.C on February 28, 1919 during President Wilson’s “Welcome Home Review,” a nationwide day of rejoicing that celebrated the return of American service veterans from Europe at the end of World War 1. In May 1919, as part of the Fixed-wing aircraft vs. Lighter-than-air craft U.S.-British “Trans-Atlantic Air Race,” C-5 made a 1,022-mile endurance flight of over 25 hours, 50 minutes from Montauk Point, New York to St. John’s Newfoundland, Canada. However, in a sudden gale the next day. despite the best efforts of 100 sailors to hold it down. C-5 bucked and broke free from its moorings in 40 mph wind gusts and was blown out to sea. (with no one on board.) Ironically, the Navy Department gave the “go-ahead!” for this U.S. Navy blimp to begin its first ever lighter-than-air craft flight across the wide Atlantic to Ireland, on the very same day the pilotless, U.S. Navy blimp freed itself, sailed aloft and was lost forever over the vast ice-berg strewn ocean.

On July 8, 1919 Lieut. Learned was flying C-8, the largest blimp of its type yet produced, from Cape May to Washington D.C. The airship broke its rudder, and was forced to make an emergency landing at the Army post at Camp Holabird, Maryland. While landing in an open field, the blimp’s hydrogen-filled gas bags expanded, the envelope had torn and the airship blew up due to the extreme heat of the day; several civilian spectators in a crowd of 75 people (including children) standing by and watching the landing were injured by the force of the hot gas blast. A half-a-mile away windows in a house were shattered.

Following C-8’s accident, and after being awarded the AFC from the British government in November 1919, Lieut. Learned, U.S.N.R.- F-C, was detached from (NAS) Cape May, New Jersey (Lighter-than-Air) and sent to (NAS) Bay Shore, (Seaplanes), Long Island, New York.

Soon thereafter, Lieut. Learned transferred to the U.S. Army Aviation Corps. Following his military service, he became a board member of the company that built and opened Elmira New York’s commercial airport in 1927. He married Alise Yeats Brown, raised a family. and had a successful business career. On August 29, 1965, he died at age 69 in Elmira, New York.

****

BKM 10/02/2020