MODEL STUDENTS – Four British WAAFS study a model of a Barrage Balloon (photo: IWM) WAAF stands for Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, and these airwomen worked with the Royal Air Force during World War II.

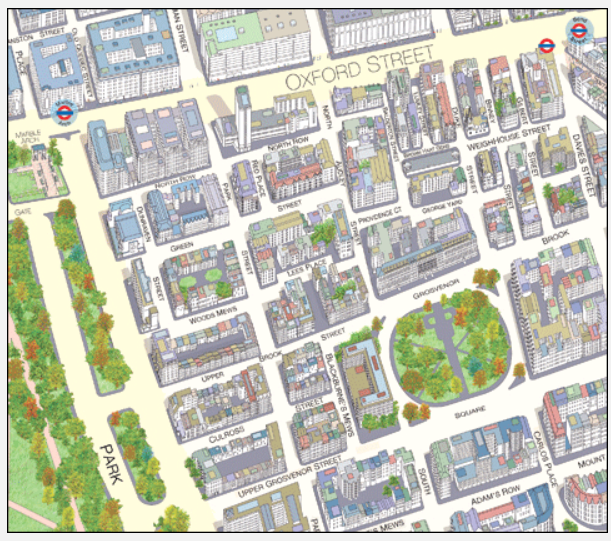

U.S. Ambassador John G. Winant (Ambassador to Great Britain from 1941-1946), living in London in an apartment above the U.S. Embassy overlooking Grosvenor Square during the Second World War, wrote the following about this Royal Park’s garden:

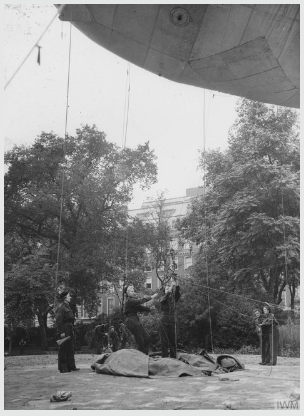

“In the Battle of Britain, the lovely garden in the center of Grosvenor Square – [pronounced Grove-nor] had been turned to more practical use. A group of W.A.A.F.’s and the blimp they called “Romeo” took shelter there. These W.A.A.F.’s were the first women’s crew to man a blimp. They lived in low wooden huts which covered what were once flower beds around the parkway. Diagonally across from the Embassy, General Eisenhower later established his headquarters and Admiral Stark had a building next door which housed the naval mission. On the other side of the square were further military installations and offices occupied by the overflow from the Embassy itself.”

U.S. Ambassador John G. Winant — A Letter From Grosvenor Square Hodder & Stoughton, 1947

During World War II, the U.S. Embassy building was located on Grosvenor Square in the “posh” Mayfair district of London’s West End. Adjacent to it, in the Navy Building, was the home of SHAEF Headquarters where planners envisioned operations for the invasion of Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

GENERAL EISENHOWER’S SUPREME HEADQUARTERS ALLIED EXPEDITIONARY FORCES (SHAEF)

SHAEF COMMANDERS AT GROSVENOR SQUARE, LONDON (photo: British Army) Left to right: Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, Commander in Chief, 12th US Army Group; Admiral Sir Bertram H. Ramsey, Allied Naval Commander in Chief, Expeditionary Force; Air Chief Marshall Sir Arthur W. Tedder, Deputy Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Commander in Chief 21st Army Group; Air Chief Marshall Sir Trafford Leigh- Mallory, Allied Air Commander, Expeditionary Force; and Lieutenant General Walter Bendell Smith, Chief of Staff to General Eisenhower. 2 Jan. 1944

In July 1942, General Eisenhower was in London. According to historian George Johnson, “On his first day on the job, in his new office, on the second floor of a row of flats at 20 Grosvenor Square, overlooking a little park where barrage balloons tugged at their anchors, General Eisenhower set his staff straight. Bankers hours were out: henceforth, they would operate a seven-day work week. So were “long liquid lunches and early cocktail hours.”

Between 1942 to 1944 at Grosvenor Square, SHAEF Headquarters was the hub of Anglo-American cooperation and the primary “nerve center” of Allied Command, where staff was planning the cross-channel invasion.

The U.S. Office of Strategic Studies (OSS), the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), had offices at 70 Grosvenor Street; its London head was David K.E. Bruce who coordinated espionage and sabotage activities with the Resistance in France.

The United States has been associated with Grosvenor Square since the late eighteenth century when John Adams, the first U.S. Minister to the Court of St. James’s, lived from 1785 to 1788 in the house which still stands on the corner of Brook and Duke Streets.

The following article from World War II appeared in The Guardian (London) newspaper. Written in 1942, relates how dramatically life changed with the arrival of hundreds of American servicemen at Grosvenor Square.

LONDON’S “LITTLE AMERICA”

Growing Colony of “Eisenhower Platz”

The Guardian (London, England) 14 December 1942, p.4

Englishmen still call it Grosvenor Square, but to the growing colony of Americans in London the spacious center of residential Mayfair has been in turn Roosevelt Square and Washington Square and is now “Eisenhower Platz.” to which leads to Eisenhower Strasse (or Grosvenor Street).

“Eisenhower Platz” is the heart of a square mile or so of London called “Little America” by its new residents, diplomats and doughboys, civil servants and scientists, from the Unties States, now occupying some of London’s famous houses.

AERIAL VIEW OF GROSVENOR SQUARE TODAY – During World War II, the Navy Building -SHAEF Headquarters, 20 Grosvenor Square, and the U.S. Embassy, 24 Grosvenor Square, were both situated side-by-side in the large red-brick Georgian-style building. (photo: WordPress)

The American Embassy doubled in size since last year and believed to be the biggest embassy in the world (it has fifteen second secretaries for those who like to count heads), stands in Grosvenor Square. The Harriman Mission is here and the Office of War Information. Not far away is the American Embassy to the Allied Governments.

“Little America” has a Whitehall of its own with an Economic Warfare Section, a Commission of Federal Communications, an Office of Scientific Research (to which Novel Prize winners pay unannounced visits for scientific co-operation) and petroleum and Civil Defense attachésand their staffs.

Ducal But Cold

In a discreet hotel near by General Eisenhower planned the North African campaign. In what was once a West End club, American officers have a mess, and the seniors from colonels upwards, use as a club the Park Lane house that once belonged to Sir Philip Sassoon. Large houses are used as barracks and the doughboys say, “They may be ducal, but they still are cold.”

Two of the biggest American clubs, the Washington and the Red Cross Nurses’, are in the quarter, and in the Platz itself is a recreation club for the sailors and marines. A special American post office is called “ Chicago Corner,” for Chicago is the home town of nearly all its personnel, and Englishmen who have never seen a “drug store” pass in a busy street the exterior of what was once a motor showroom and is now the nearest “Little America” can manage to drug store model. The “drug store” is called “the quarter masters’ exchange” and issues the rations of real American cigarettes, candies, and special toothpastes, which the soldiers buy under the rough and ready notion that “five shillings is a buck.”

GROSVENOR SQUARE, MAYFAIR DISTRICT, WEST END, LONDON – To the west is Hyde Park and Park Lane. (Image: Silvermaze Ltd)

There are no married quarters for the soldiers of “Little America,” for there is only one wife here, Mrs. Bryan Conrad, whose husband, a lieutenant colonel, was in England before the war as Assistant Military Attaché: but as the hotels fill up many officers are taking flats together, and the colony spreads westwards and southwards (Southern dried bread is now being served for breakfast in Kensington).

Main Street On Our Doorstep

It is a matter of speculation whether the English are becoming Americanised or the Americans anglicized in “Little America.” We are said to chew gum, go to “movies” instead of cinemas, and have adopted “You ain’t kidding?” as a phrase during the last few months. But the Americans now stand in “queues” instead of “lines,” travel by “Underground” instead of the “subway,” and indulge in “leg-pulling.”

GROSVENOR SQUARE – One of London’s famous Royal Parks. (photo: WordPress)

In summer they showed us baseball, and now in winter they are admiring our knowledge of “jive,” which for the uninitiated should be explained as the successor of “swing,” only hotter.

“I’ve got spurs that jingle, jangle, jingle” is as popular here as in America, and the visitors say we play it well. They like listening to our Hyde Park orators. Londoners have most admired the easy nonchalance with which new residents of Mayfair have sprawled on porches, ad brought Main Street to our own doorstep.

BARRAGE BALLOONS FLYING OVER LONDON (photo: IWM)

THE BARRAGE BALLOON COMMANDER WHO LED THE WAY –

ACTING AIR SQUADRON OFFICER DIANE MARY BARTON, WAAF

In August 1941, Acting Air Squadron Officer Diane Mary Barton, WAAF, was put in charge of a barrage balloon site at Grosvenor Square and 14 balloon operators, all of them women, were under her command. She later recalled her experience:

“I was lucky and got the posting at Grosvenor Square… My site was particularly difficult owing to the various surrounding streets. The 14 airwomen were well trained but, of course, not experienced. As we had the American Embassy on one side, the American marines on another, and the Japanese Embassy of the far side, it was all nerve wracking. Had we had the misfortune to hit one of the roofs it would have been put paid to headquarters. Needless to say, the atmosphere was tense at the time of Pearl Harbor.

“We had many visitors from the allies. General Eisenhower and Averell Harriman (President Roosevelt’s Special Envoy on the U.S. Lend Lease Mission) were two that I remember. The most important, as far as I was concerned, was the little man in the bowler hat with a rod trying to find the drains which were laid in the 1914 war for the Salvation Army. They were not found and, in the end, we were allowed to use the loos in one of the houses in the square. Our neighbors in the square, very naturally, did not approve of us digging holes to empty the Elsan (chemicals used to kill bacteria) in a portable lavatory.”

Grosvenor Square was surrounded by Victorian-era iron railings and Britain was short of iron and so across the country a call went out for any metal objects that could be scrapped to help with the shortage. The iron railings around the square became a prime target. However, a special order was made ensuring that the railings that surrounded the balloon and associated structures were left alone. The railings gave extra protection to the balloon girls manning the balloon.

Air Squadron Officer Diane Mary Barton related this about the iron railings controversy, “This was out of the question as far as I was concerned, so I went to the M.O.D. (Ministry of Defence) … and said they could not possible have mine, and explained about all the airwomen. I won the argument! The following day a dispatch rider arrived with an enormous padlock and chain to secure the gate. Actually, the airwomen were armed with truncheons, but only needed to knock out one person. (He was) a very bossy R.A.F. Flight Sergeant testing our security.”

Quotes taken from a letter by Acting Squadron Officer Diana Mary Barton, WAAF, O.B.E summarizing her service: The Lighter Side of My War Effort 1938-1947.

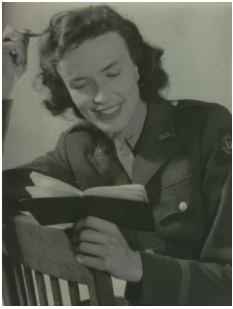

OFFICER IN CHARGE – Acting Squadron Officer Diana Mary Barton, WAAF, O.B.E., commander of the Barrage Balloon site at Grosvenor Square (photo: Barton family.) She later said, “Although we were a fully operational site, we were also used for propaganda purposes.”

The following article appeared in the Guardian (London) newspaper in August, 1941 concerns the WAAFs who manned the barrage balloon named ROMEO at Grosvenor Square:

ROMEO AND HIS JULIETS

The Guardian (London, England) 09 August 1941 p.6

The first balloon site to be handed over entirely to the W.A.A.F. is in a Mayfair square. The girls many of whom are trained and qualified in Air Force trades have christened their unwieldy charge “Romeo.” The hut in which they live is “Ye Olde Log Cabin” as though to spite its aristocratic neighbors. To some extend the W.A.A.F. is on trial here. If this barrage balloon company can stand up to the work during the winter, the W.A.A.F will take over more jobs of the kind, to release men for other duties.

LIFE WITH “ROMEO”: THE EXPERIENCES OF THE WAAFS WHO OPERATED THE BARRAGE BALLOON AT GROSVENOR SQUARE, LONDON

KITBAG ON HER SHOULDER – A young woman in the WAAF reports to duty at a Balloon Site in England (photo: IWM)

North American war correspondents were utterly fascinated by the sight of the English airwomen who operated a barrage balloon named “ROMEO” at Grosvenor Square, London. These WAAFS belonged to the 906th Balloon Squadron, with its headquarters at Hempstead. Their story was popularized throughout the United States and Canada in the syndicated press between 1941-42 in the following three newspaper articles:

BARRAGE BALLOON GUARDING U.S. EMBASSY IN LONDON IS MANNED ENTIRELY BY WOMEN

By Kathleen Harriman

The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois) 17 November 1941, p.16

Have you heard about Romeo?

I thought not. Well, Romeo is the barrage balloon that stands guard over the American embassy. He lives in Grosvenor square down behind those chestnut trees.

Actually, he’s a very special balloon, all the other balloons over London have feminine names. They are Mae West, Melinda, and Suzy. Perhaps you wonder why. Well, Romeo’s keepers are girls-members of the Woman’s Auxiliary Air Force service.

This morning I walked down and watched them put Romeo to bed. It’s quite a complicated process at that. Takes eighteen girls to do it and on windy days he puts up a big fight.

The eighteen WAAFS, in their practical but not too clean battle dress, worked with almost clocklike precision. A sergeant (yes, a girl sergeant) stood in the center of operations with a megaphone.

“O ROMEO, ROMEO… WHAT IS IN A NAME?” – WAAFS at Grosvenor Square adjusting the mooring lines attached to their Barrage Balloon named “Romeo.” (photo: IWM)

Girls Rush to Posts

“Haul in on bollard!” meant nothing to me, but the girls jumped to their posts at the guy ropes and the girl at the winch started the engine and slowly Romeo descended into our midst.

He’s got a right to be proud. He’s one of the balloons chose for an experiment- an experiment that has proven successful after a month of operation. This guardian of our embassy is one of the four barrage balloons in all Britain to be manned by women. Manned by women – perhaps that sounds a little odd, but that’s what the Air Force calls it. Manned by ACWL 1. That, I learned, stands for Aircraft Women Class 1. In other words, the best.

The physical requirements for WAAFS balloon barrage crews are not as exacting as I’d anticipated. They aren’t the country girls, used to working in the open air, I’d visualized.

Team Work Required

Asking around I found that most of them had been seamstresses or sewers of sorts, who had originally signed up to do repair work on the balloons. They weren’t a particularly hefty lot. Teamwork, not brawn, is required. They work in pairs at the ropes and today being fine their work was easy.

No, they wouldn’t give up their job for the world. They enjoy, too, the distinction of being the WAAF crew in London.

One girl told me: “I’d be miserable if I were transferred. I’ve become sort of attached to Romeo. He’s so homely and helpless.”

Another reason, too, maybe? I noticed she was smoking American cigarettes. There are all sorts of advantages to operating the balloon that files over the American embassy!

BALLOON BARRAGE WOMEN’S SERVICE

The Ottawa Journal (Ottawa, Canada), 3 January 1942

London- This barrage balloon used to be called “Gloria”, but now its name is “Romeo”.

The reason? It has been taken over by members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, the first air-women to displace men in control of a balloon. The men always referred to it as “she,” but when the women took over they changed it to “he”.

The WAAFs send it up, keep it in the air, haul it down and tether it. They guard it in twos, day and night there are no men on the site at all.

The crew includes Winnie, 18 from Bow in London’s East End, who used to be a dressmaker. Diana, in charge of the crew; Sergeant Selina, a former Peckham shirt machinist, and Corporal Lena, owner of a Liverpool tailoring business, are others in the team.

A FABRIC WORKER MAKES REPAIRS – A WAAF Balloon operator at a sewing machine stitches a patch on a barrage balloon (photo: IWM) The fabrication, repair, servicing and launching of barrage balloons was conducted at R.A.F Base Chigwell in Epping Forest. Most of the airwomen had worked there before being assigned to operate Romeo, the barrage balloon at Grosvenor Square, London.

Most of them have been on airplane fabric mending and Winnie has patched more than 300 balloons. Hauling a balloon up and down is easier than fabric work, they all say.

A group captain, commander at the big London balloon centre, said, “I’m willing .. to bet the women won’t lose more balloons than the men; they may lose fewer”.

PRETTY WAAF GIRLS TAKE CARE OF A LADY-KILLER-ROMEO

(BALLOON BARRAGE)

By Inez Robb

The Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York) 16 January 1942, p.9

London- (INS) – All Romeos, taking color from their original prototype, have been temperamental, domantic and unpredictable guys.

The Romeo of a certain London square (name deleted by censor) is no exception. Like all Romeos, he is a lady-killer. It requires the constant ministrations of a crew of women to keep him tractable and happy. Even so, he is apt to behave very badly on occasion and cause his girl-friends excessive work, worry and not a little anger. These occasions are usually brought on by high winds, which always gives Romeo ideas of his own. Romeo is a handsome barrage balloon in the very heart of London.

Indeed, Romeo and his harem of WAAF attendants live in a fashionable little square, comparable in size to New York’s Gramercy Park.

“For Heaven sake don’t let Romeo knock down the embassy chimney pots!” More than one officer has cautioned her group when Romeo has been behaving badly in a wind. So far, this minor catastrophe has been avoided. The chimney pots are still intact.

Save for windy weather, Romeo is pat to be an attractive, agreeable fellow who closely resembles a huge silver whale accidently strayed from Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade in New York.

Worked in Cold Fog

I visited the balloon site on the coldest day I have yet experienced in London. The fog was as thick and damp as a wet blanket. My feet were encased in stout, lined galoshes. I shivered uncontrollably in a heavy fur coat, a wool suit, a sweater, and suitable undergarments of flaming flannel.

The girls working over Romeo, momentarily grounded for morning inspection, put me to shame. With sleeves rolled up to the elbow, they inspected and spliced his ropes and wires. Skull caps sat jauntily on their young heads and ears and noses were pink with cold as they deftly fed hydrogen into is innards.

Cold to my very marrow, I watched these girls work on Romeo and on the winch that raises and lowers him. They seemed an Amazon crew until I got a bit closer. Then I realized that these young girls-you have to be young to do this heavy work- in their soiled, navy blue service dungarees were padded with goodness knows how many layers of clothing beneath their coveralls.

INSPECTING THE PICKETING LINES – A WAAF does a pre-flight inspection of a barrage balloon (photo: IWM)

They were cold as I. But they went about their duties efficiently, cheerfully. It is obvious why this group of girls, whose work with Romeo was experimental as first, has proved to the country, the R.A.F. and the WAAF that women, properly trained, can replace thousands of men hitherto detailed for this vital service.

Girls Love Hard Work

A woman in dungarees, beneath which she has stuffed every article of warm apparel she owns, is not a particularly chic sight, especially when her feet are encased in rubber boots, from whose tops ooze the heaviest of gray woolen sox! But I noted that every girl, no matter how broken her nails or greasy her hands as she went about her particular job, had a careful coiffure, in some cases as elaborate as any film star. These girls have no time to powder their noses in the middle of their job, but there are traces of powder that had been applied at dawn.

ADJUSTING BALLOON RIGGING – A WAAF balloon operator adjusts the rigging of their barrage balloon. Note the parked “Eagle” hydrogen cylinder trailer in the background, and the Flight’s mascot dog. (photo: IWM)

Thirty minutes after I arrived, a Y.W.C.A van drove into the once sacred confines of the square with hot, mid-morning tea and buns for these girls. The crew- that is, the plain buck privates in the WAAF-and I sat in the tool shed and talked while we all shivered together and drank the welcome, scalding tea.

The verdict- with no officers near to hear it- is that the girls love the work, hard though it is. Not a one but led a humdrum life in home or factory before the war began. This is the nearest thing to personal adventure they have ever tasted.

Before the war one of them lived in Durham and worked in a factory manufacturing handbags. Now she has food, clothing and shelter free and pay amounting to about $9 every fortnight. She has one day off in every seven and one week off in every three months.

Attend Training Course

A husky blond girl was a street car conductor in Birmingham until five months ago. Another merry Yorkshire lass was a tailoress before she volunteered to care for Romeo.

“Man-like, you have to give Romeo his head, but draw a firm ad gentle reign on him,” she said as she sipped her tea.

A sparkling blond who has been in the WAAF for 15 months has been oiling the machinery, and had only had time to wipe the worst of the black grease from her hands before the mug of tea was thrust into them.

It is the winch, now used for lower and raising barrage balloons, that makes it possible for women to do this work. All minor repairs on the mechanism are done by the women themselves.

HAULING DOWN A BARRAGE BALLOON – Trainees at Balloon Command Grouping, 1 BTU (Balloon Training Unit), R.A.F. Base Cardington, Bedfordshire.(photo: IWM)

Women who enroll in the WAAF for balloon barrage work go to a training center for the usual 14- day disciplinary course at a regular WAAF depot. There they received their kits, learn drill and attend lectures. At the conclusion of this preliminary training, they are sent to a training center for a course in balloon operation. This course produces a woman fully competent to take her place in a balloon crew.

Three of Romeo’s crew are married. One of these, a pretty girl with light, curly hair is typical. She joined the WAAF when her husband joined the RAF as a gunnery officer in anti-aircraft work.

“The girls are very reliable” said their boss, a young and pretty section officer. She was, believe it or not, a ballet dancer before she joined the WAAFs.

Quarters Cold, Barren

One quickly learns that women in the auxiliary forces lead a Spartan life at best. The girls on this balloon site live in one of the mansions on the square. That sounded very good until I saw the quarters. They eat, sleep and have their recreation room in the basement of the house.

It was bloody cold the day I was there. The dormitory, with its double-decker beds, looked barren and their small sitting room cheerless. Their meals are eaten in the tremendous kitchen that once served this mansion. An old mountainous coal stove crouches like a sullen elephant along one side of the room.

The only room in this basement which was half-way warm was the small kitchen, fitted up in the rear of the old one, where two WAAFS were preparing luncheon for the crew. (All have their turns at kitchen duties.)

Back in the square, on the site of the barrage balloon, the girls have a recreation hut called Ye Olde Log Cabin! It too, contained no luxuries, although the girls had fitted up a ping pong table in one corner. A small stove seemed to have given up all attempt to heat the room. A radio, a gramophone, a few chairs and a table completed its furnishings.

Back of this room is a small dormitory where those on night duty sleep – half dressed to be ready for an emergency.

“The girls patrol the site at night to prevent any damage to Romeo or to the winch,” the section officer explained.

She picked up a policeman’s billy from one of the dormitory cots.

“This is the weapon with which the WAAF walks her night patrol,” she explained.

PACKING – WAAFs folding a barrage balloon (photo: Cecil Beaton, IWM)

“MARINES MAKE NO GAIN AT BRITISH WAAF CAMP”

Americans Lose No Time In Getting Acquainted With Girls In England, But It Was Necessary To Call a Cop To Inform Them They Were Out of Bounds.

By Gault MacGowan

(North American News Alliance)

The Times-Tribune (Scranton, Pennsylvania) 23 October 1942, p. 26

With the WAAFS (Passed By Censor), Oct 2, 1942 (Delayed). —The Marines have landed. The situation is well in hand. This is a historic saying but here is a story of how the marines were once defeated.

They had just landed in Britain and they were defeated by the WAAFS. These girls of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force were in charge of a kite balloon which protected the marines’ headquarters against attacks by hostile dive bombers.

This is the story as the girls told it to me: “As soon as the marines arrived and had been dismissed off parade, they strolled over to visit our camp. Ordinary soldiers would not have been allowed in-but the American Marines, well, you know what they are, they would not take no for an answer, and we don’t want to seem discourteous to visitors, especially such welcome allies. When we threw them out by the main gate, they would come in at the back, and if one marine was rebuffed at one place another would stroll in innocently at the back and pretend he did not know the Ballroom site was out of bounds. Before they arrived, we did not bother to lock the gates of the site at night. But we soon had to do so.

BALLOON HANDLING – A WAAF balloon operator inspects a rope with sand bags for ballast on a barrage balloon (photo: IWM)

“One of the girls would be tugging at a sandbag or a cable one minute; the next a stalwart marine would have edged in and be doing their job for her with a friendly “Let me help you out, sister!” Well, of course it was very lovely of them but it was terribly frightening. We lived in constant alarm lest one of our officers should arrive and accuse us of encouraging their attentions!

Had To Call Cop

“Finally, it got so bad we decided, Anglo-American relations or not, we should have to stop it. So as soon as the marines arrived one of us would slip out and fetch a policeman. The policeman usually managed to convince them they had no right to be about the site. So, between us and the bobby, we repulsed them. But the trouble never really ended till we got the gates locked at night.”

But don’t think these WAAF balloonists are not romantic. They are. On this particular site they have had two balloons since they started. They called the first one Romeo. He lasted for 178 days. Then they lost him.

“PULL HARDER!” – WAAF balloon operators struggle to haul down a barrage balloon (photo: Crouch F/O, IWM)

“You don’t feel really pukka until you’ve lost a balloon,” Corporal Jessie told me. She is just nineteen and has been in the WAAFS for a year.

When they got their replacement balloon it was called, by common consent, Romeo.

Except for chasing off marines, the toughest assignment the girls have is on a windy day. Then flying the big kite balloon is a strain.

AIRBORNE – WAAF balloon operators stabilizing a big barrage balloon on a gusty day (photo: IWM)

“However carefully the girl on the winch pays out the cable, if you are not careful you may be jerked right off your feet and carried up in the air quite a way,” said Margaret, a girl from Belfast. “I saw one girl carried up about twenty feet before she fainted and fell off. But such happenings make the life interesting, and we all love it because it’s all in the open air and very healthful. We all feel much better than when we used to work indoors.”

EARLY MORNING INSPECTION IN THE PARK (photo: IWM)

When the balloon barrage first started as a feature of the English landscape it was entirely staffed by men. Now the only man left in this flight- as they call the balloon platoon- is the commander.

“My flight has been entirely WAAFED” was the way he put it.

The best assignment the girls can get is to be put on the London balloon barrage. There they live the open-air life in one of the parks. And there is lots of recreation in the evening. They are frequent visitors at the United States Army clubs when dances are organized.

VEGETABLE GARDENING ON A CASUAL DAY OFF – WAAF balloon operators tending to their victory garden (photo: IWM)

Concentrate On Gardens

Sometimes, owing to weather or raid conditions, balloons may not fly for as long as a week. It is no good putting them up if the Nazis are occupied elsewhere. Then the girls concentrate on the vegetable gardens they are cultivating round their sites. Or they take turns in doing cooking. Unlike a man’s army, there is lots of competition for this job.

However, on this particular balloon site they had to have a man cook to come along to show them how to do it. All the girls knew how to cook a dinner for two but they were not so good when it came to turning military rations into a meal for twenty or thirty.

It is fun to cook a steak or a roast, but, when you get a side of beef in bulk, you may well wonder where to begin on it. Then there are problems of cooking in camp kitchens that the apartment housetrained Chef never heard of.

Outside such matters of training, the girls have one worry. They are all putting on weight in balloon barrage business.

“We seem to put on weight at once and in a few weeks our uniforms look too small and too tight for us,” Jessie told me.

Jessie was a corsetiere before the war began. She ought to know what it has done to the feminine figures over here. Instead of drawing in their belts they have been busy letting them out.

From corset making, by the way, Jessie went into a fabric factory where balloons were repaired. She got so interested in them that she decided to volunteer to fly them. Now here she is on the site.

Twenty-six-year-old Elsie and twenty-one-year-old Dora were two other gals I talked to. What they liked about the life was the drill and games. They play net ball and tennis.

But they all seem rather shy about opening their hearts to me. That is because a war correspondent visiting the balloon site has to be heavily chaperoned. Escorting me was the flight commander, a man, an assistant section officer, a woman, and two WAAF public relations officers. My article had to be written in triplicate and submitted to a board of censors.

The marines have landed- but their influence is nil around here.

A former American wartime news correspondent in England, Jack Kofoed, writing in his weekly column in The Miami Herald in 1948, offered these personal musings about his time at Grosvenor Square and his memorable experience of seeing the WAAFS there:

BARRAGE BALLOON IN GROSVENOR SQUARE, LONDON

By Jack Kofoed

The Miami Herald (Miami, Florida) 5 April 1948, p.35

They are going to erect a statue to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in London’s Grosvenor Square. During the war the famous old square grew shabby, and its only decoration then was a barrage balloon a crew of WAAFs in coveralls raised and lowered each day.

It seemed a little strange that, with all their bombing, the Nazis never hit Grosvenor Square. They knew that, before the invasion, it and the Eighth Air Force headquarters at Kingston were the nerve centers of the American Expeditionary Force.

Many buzz bombs [German V-1 rockets, unguided flying bombs launched from France] must have been timed to land there. Hundreds sailed over the square. Some hit 15 or 20 blocks away, but not a single one struck Grosvenor. Maybe it had a charmed life. Anyway, the square went through the entire war unhurt.

At that, the statue of Mr. Roosevelt will be a better decoration than the barrage balloon… but, the WAAFs, even with their oil-smeared faces and dirty coveralls…were not bad, at all.

A SENSE OF AMAZEMENT – A crowd of Londoners watching a silvery barrage balloon go up above the Tower of London (photo: IWM)

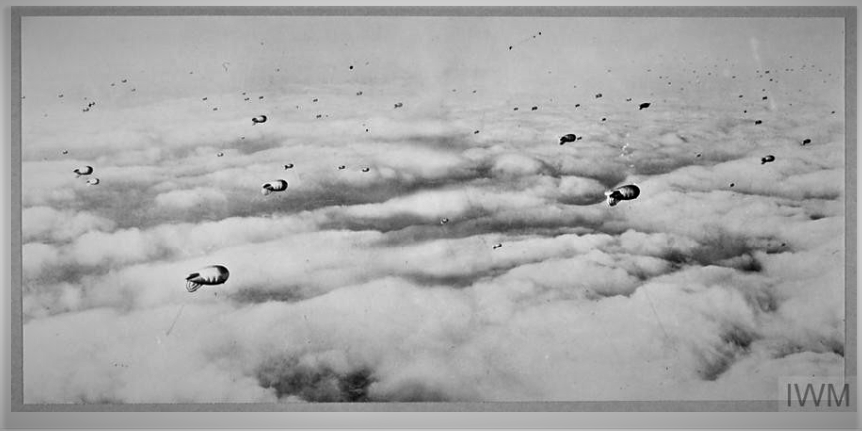

The R.A.F.’s Balloon Command first organized the UK’s barrage balloon defenses in August 1939. As World War II raged on, barrage balloons were operated throughout Britain by the WAAFs and played a significant role in anti-aircraft defenses. Barrage Balloons restricted the freedom of German dive bombers, often forcing them to fly different routes to a particular target. By forcing German planes to fly above 5000 feet, they reduced the accuracy of their bombing and also made them more vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire.

“UMBRELLA DEFENCES OVER LONDON”- The Royal Air Force’s Mark VII Barrage Balloons At 5,000 Feet, arrayed as a part of in the air defenses over London, 1944 (photo: IWM)

R.A.F. Balloon Command started operating barrage balloons across Britain by 1940 and quickly deployed 1466 balloons, including some 450 over London.

The British Government Information Ministry issued a press release, dated May 4, 1940, that said,

“Barrage Balloons, placed in strategic points all over the country, are linked by an elaborate system of communication, and the balloons can be raised to a great height – another very close secret – in a few seconds.

“Today more than 40,000 men are flying balloons. On the outbreak of war, the barrage balloons went into action and thickets of lethal cables rose to the skies.”

“In the Balloon Centre (R.A.F. Base Chigwell) on the fringe of London, girls of the British Women’s Auxiliary Air Force work side by side with the men of the R.A.F. in repairing balloons. There are 90 W.A.A.F’s there and the men’s number totals about 2,000.”

THE LONDON BLITZ: THE FIRST NIGHT’S BOMBING, 7 September 1940 (photo: German Luftwaffe / RAF Museum) – A German Luftwaffe bomber – Heinkel He 111 – flying over Wapping and the Isle of Dogs in the East End at the start of the Luftwaffe’s evening bombing raids over London.

During London Blitz, in the first phase of the Battle of Britain (from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941), barrage balloons became an integrated, along with radar, ground spotters, Spitfire or Hurricane fighter aircraft, anti-aircraft gun batteries and searchlights, into London’s extensive air defenses against the German Luftwaffe’s bombers attacks. Throughout this perilous time, all balloons were operated entirely by men.

DIVE BOMBER – A Luftwaffe Heinkel III Bomber pilot on a raid over England, 1940 (photo: Bundesarchiv)

In August 1941, at Grosvenor Square, London, women in the WAAF were the first in the country to fly barrage balloons in round-the-clock operations. After much discussion, it was found that fourteen women, rather than twenty as initially thought, could replace a ten-man team. Brains and technology, instead of shear brawn, was employed with the advent of a highly efficient cable-winding winch system to rapidly haul down the balloons. Being highly visible, barrage balloons bolstered the morale of the British people.

Barrage balloons played a significant role in Britain’s anti-aircraft “umbrella” defenses during the entire war. The balloons were a familiar sight throughout Britain, on mainland Barrage Balloon sites, until 1945, at the end of World War II.

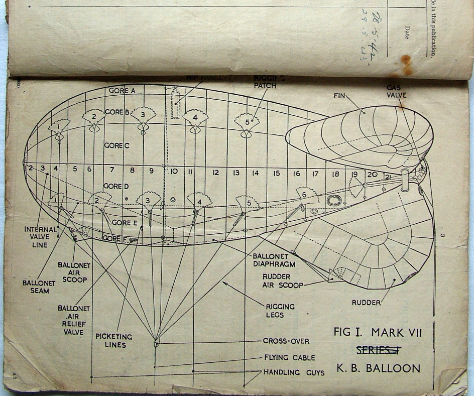

The R.A.F.’s barrage balloon was originally designed and developed in 1934 at Cardington and they were called the “LZ (Low Zone) Kite Balloon.” These large hydrogen-filled balloons were tethered to the ground or, in the case with Royal Navy warships and merchant ships, to the deck of a ship by way of metal cables. They were deployed as a defense against low-level air attack, damaging aircraft on collision with the cables or, at minimum, making flying in the vicinity of them highly treacherous.

Nearly 3,000 hydrogen-filled barrage balloons were operated by WAAF airwomen protecting cities and strategic sites across Britain by 1944.

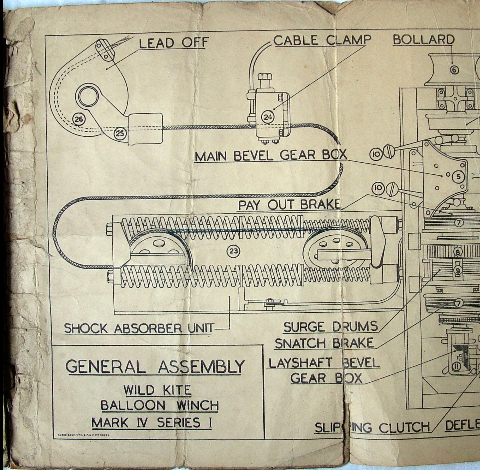

A FIGURE OF A MARK VII BARAGE BALLOON FROM A ROYAL AIR FORCE HANDBOOK in the papers of WAAF Vera Ash 460447 (historicflyingclothing.com)

A FIGURE OF THE BALLOON WINCH ASSEMBLY in the papers of WAAF Vera Ash 460447 (historicflyingclothing.com)

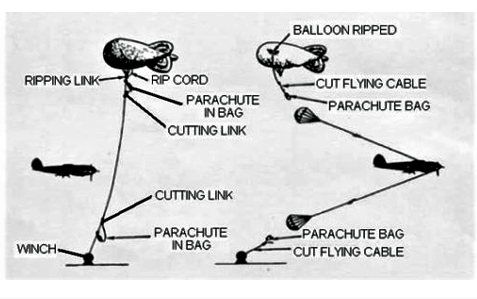

HOW PARACHUTES AND CABLE (PAC) BARRAGE BALLOONS ACTUALLY WORKED (Graphic: R.A.F. Museum)

Canadian reporter Jody Paterson met in the year 2000 with a group of 16 veteran WAAFs. These English women – many of whom had been barrage balloon operators during World War II – were by then in their 70s and 80s. After the war they had come to Canada as young war-brides who had married Canadian servicemen in England, others had emigrated to Canada for other reasons. She recorded their wartime stories and shared them in the following article:

GIRLS IN A MAN’S WAR – Memories Rekindle a Time of Passion and Adventure in Britain

By Jody Paterson

The Times Colonist (Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) 3 November 2000, p. A3

… The Second World War was gripping the globe and Britain’s men were needed in combat, leaving the government little choice but to draft single women aged 17 and up to keep the military machine running and the munitions factories open. Weaker sex be damned; women were needed in the field.

More than 1,000 WAAFs were assigned over the course of the war to operate barrage balloons, the gigantic tethered blimps used to thwart low-flying enemy bombers. Others worked at switchboards in underground bunkers, ran wireless equipment, repaired instruments. Plotters such as Pat Ashbaugh learned the intricacies of exactly pinpointing the whereabouts of planes overhead based on a constant stream of information from spotters.

In the end there would be more than 100 trades that WAAFs would learn, and the work was unrelenting- long hours, terrifying responsibility, one lousy week off a year and only the occasional 48-hour pass, all for just nine shillings a week.

But the reward was suitably significant: Freedom unlike anything a young girl of the time could have imagined, including the flattering attentions of any number of homesick boys.

WAAFs typically lived in 36-bed Nissen huts near their postings, most often a long way from home and with minimal comforts. Bath time was once a week and the depth of the water strictly regulated, with an extra inch for that “time of the month.”

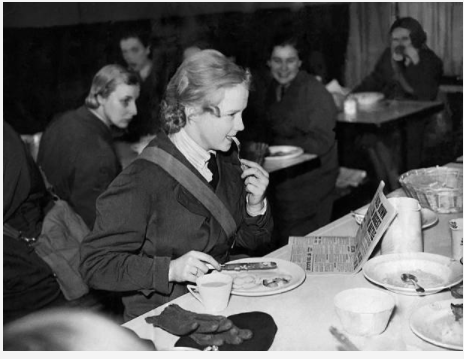

MORNING BREAKFAST – A WAAF takes a bite to eat with “a spot of tea,” while reading a tabloid newspaper. (photo: IWM)

The food was awful; Betty Dimond says her squadron dubbed one of the dishes “mashed monkey” after everybody gave up trying to figure out what meat it was made with. The kidney was like charcoal. The fried bread it was served on was worse. And those horrible creatures that lived above the wall near the stove-steam bugs, the girls called them- were always dropping into the food.

Terrible things happened, as they always do in war. WAAFs died in enemy attacks, and so did so many of the men they loved. Brenda Beech’s barrage-balloon unit near Liverpool inadvertently brought down two Allied planes when the cocky young pilots ignored the signals that the balloons were going up. Twelve people died as a result, and Beech remembers having to duck stones thrown by the local children who blamed the WAAFs for the deaths.

A NIGHT OUT AT A MIXER – An All-Ranks Saturday Night Dance (photo: IWM)

But there were dances most Saturday nights and no end of handsome men to hold onto for the lonesome, invariably Who’s Taking You Home Tonight? There were forbidden silk stockings to liven up the standard-issue underwear the boys had dubbed “passion-killers,” and sometimes even a pair of those sexy ones with the seams up the back to drive a million boys mad.

“The station where I worked had hundreds of men and 31 WAAFs,” recalls Norma Curry fondly. “We’d be at our house and somebody would call out, ‘There’s a fair-haired sergeant here-who’s date is he?’ and a bunch of girls would be looking out saying, “Uh, let’s see…maybe…no, I don’t think that one’s mine.’”

There were great friends and lots of laughs, like the time Curry forgot she’d stashed her powder puff in her gas mask and almost suffocated during a surprise drill. And there was love, or at least what passes for it, when two lonely people are far from home.

“I remember one woman saying to me, “I came out of the service as a sergeant. What did you come out as?’” recalls local WAAF president Betty Gaynor. “Pregnant, I told her.’”

The lunch crowd has thinned at the Swiss Chalet by the time the storytelling is winding down. A small crowd of husbands is massing at the restaurant entrance; their wives, still flushed from recollections of old romance and bravery, glance over to check whether any are here for them, and then go on talking anyway.

Almost 60 years have gone by since those days, and not all of them kindly. But for a moment all the beautiful girls of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force have got the boys waiting again.

WINNERS – Two WAAFS celebrate VICTORY IN EUROPE (VE DAY) in London on 8 May 1945 (photo: IWM) After the surrender of Germany, World War II ended in Europe, but it would take another three months before the war ended in Asia.

******

THE AMERICAN WAR CORRESPONDENTS

This article presented three feature stories – recorded verbatim in their entirety – by Kathleen Harriman, Gault MacGowan, and Inez Robb – about the airwomen who operated the barrage balloon named ROMEO at Grosvenor Square, London from 1941 to 1942. The careers and wartime experiences of these American war correspondents in World War II are summarized as follows:

KATHLEEN HARRIMAN, AUTHOR OF “BARRAGE BALLOON GUARDING

U.S. EMBASSY IN LONDON IS MANNED ENTIRELY BY WOMEN “

KATHLEEN HARRIMAN (photo: Harriman Institute, Columbia University

Kathleen Harriman (1917-2011) was born into a patrician family. Her father, W. Averell Harriman, came from the fourth wealthiest family in America, was the CEO of the Union Pacific Railroad, the head of the New York investment banking firm, Brown Brothers, Harriman, and was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Special Envoy in London. At age twenty-three, in 1941, “Kathy” joined her father there, (where he served as principal liaison between President Roosevelt and the British government, especially Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the primary administrator for the Lend-Lease Act.) The relationship between FDR and Churchill was sometimes testy, so her father was sent there to smooth things over. She had only planned to stay a short time but instead decided to become a news reporter for Hearst’s International News Service and Newsweek magazine (which her father half owned).

A Vanity Fair Magazine article declared in 2011, “Kathy had no real reporting experience, but her father had managed to pull a plum assignment for her: she would write of the heroics of the Englishwomen. The series—for Hearst’s International News Service—would be called “The British Woman at War.” “Just give us everything you can observe and think of, sobbing all over the page, one editor would later instruct her.” At the London office of Newsweek, during the winter from 1942 to 1943, while the bureau chief and the correspondents were away in the war zone, she worked long and hard 12-hour days. But she was not absent from London’s highest social circles – she maintained close relationships with Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his family, the press tycoon Lord Beaverbrook, the Minister of Information Brendan Bracken, as well as many prominent leaders of Britain’s war effort.

KATHLEEN HARRIMAN WITH “THE DAMES OF D-DAY” – Kathy is seen third from the left. (photo: Lee Miller Archives) – In this photo, taken on the rooftop of the U.S. Embassy in London, Kathy sits and smiles with her fellow American female war correspondents/ photo-journalists. From L to R: Women war correspondents accredited by the US Army: Mary Welsh, Dixie Tighe, Kathleen Harriman, Helen Kirkpatrick, Lee Miller, and Tania Long.

When her father became U.S. Ambassador to Russia in 1943, he took her along to act as his hostess at Spaso House, the grandiose but dilapidated U.S. Ambassador’s residence in Moscow. Ambassador Harriman was nicknamed by embassy insiders, “the Crocodile” for his sudden dictatorial outbursts. George F. Kennan, the senior career Foreign Service officer in Moscow, recalled, rather sardonically, that thankfully, Kathy in –very un-Harriman-like— fashion had a sense of humor.

Kathy assumed her duties at the U.S. Embassy with elegance, style and grace – seasoned with a touch of panache – to override the somberness and restraint of the Kremlin’s “nomenklatura” – Russia’s ruling elite. Writing to her sister Mary on Thanksgiving Day in 1943, she revealed, “Maybe I haven’t made life in Moscow as enticing as I intended. But by comparison to what critics painted it to be, it’s damn near paradise.”

She was particularly impressed by Comrade Joseph Stalin, the unrivalled “Red Tsar” of Soviet Russia. In a letter she commented, “He was in top form—a charming, gracious, almost benign host, I thought, something I’d never thought he could be. His toasts were sincere and most interesting…”

“The Boss” responded to her friendliness by giving her an unexpected gift. Knowing that she was an equestrian, Stalin gave her am magnificent cavalry horse that had served at the Battle of Stalingrad. She named the horse “Boston.”

After the Yalta Conference in early 1945, between FDR, Churchill and Stalin, however, she finally grew suspicious of the Russian dictator’s real motives, especially after he revealed his quest to dominate Eastern Europe.

During her stint in Moscow she coordinated the social schedules of many important American visitors, including Harry Hopkins, FDR’s Secretary of Commerce, and President’s closest advisor on foreign policy and the supervisor of America’s $50 billion Lend Lease military program to the Allies; Lillian Hellman, an American playwright noted for her communist sympathies and political activism; James B. Conant, president of Harvard University; Bill Donavan, head of the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS); James F. Byrnes, U.S. Secretary of State after FDR’s death in 1945; and, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, SHAEF commander.

“I still think I ran a reasonably successful boarding house.,” Kathy later recalled.

KATHLEEN HARRIMAN IN MOSCOW – General Dwight D. Eisenhower with W. Averell Harriman, U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union (fourth from the left) and his daughter, Kathleen Harriman, after watching a sports parade in Red Square during the general’s visit to Moscow after the war, 1945. (photo: Eisenhower Presidential Library)

REFERENCES

Geoffrey Roberts, The Wartime Correspondence of Kathleen Harriman, Harriman Magazine, Harriman Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY, pp. 16-17, 20

Marie Brenner, “To War in Silk Stockings,” Vanity Fair, November 2011

https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2018/04/to-war-in-silk-stockings-kathleen-mortimer

Obituary of Kathleen H. Mortimer, 2017-2011, Smith, Seaman and Quakenbush Funeral Homes, New York

https://ssqfuneralhome.com/tribute/details/1272/Kat,hleen-Mortimer/obituary.html

GAULT MACGOWAN, AUTHOR OF

“MARINES MAKE NO GAIN AT BRITISH WAAF CAMP”

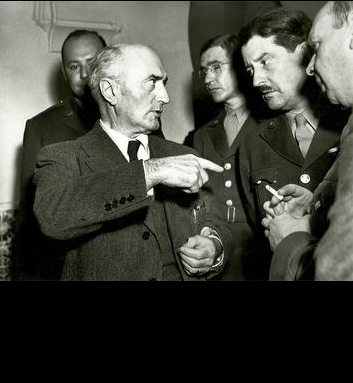

GAULT MACGOWAN (the man with the mustache on the right) listens carefully to Admiral Jean Louis Francois Darlan, the French Vichy Naval Minister (photo: WP:NFCC)

(This photo of Admiral Darlan was taken in Algiers on December 16, 1942, only eight days before his murder. He was assassinated by a French monarchist on Christmas eve. Admiral Darlan was a notorious collaborator with Nazi Germany. The French Fleet under his command anchored at Oran, Algeria had been destroyed by the Royal Navy on July 3, 1940. He was captured by the Allies in Algiers on November 8, 1942, and thereafter, after cutting a deal with General Eisenhower, he had ordered all Vichy forces in North Africa to join the Allies.)

Alexander Gault MacGowan (1894-1970) was one of the leading war correspondents in World War II. He was British, born in Manchester, England, of Scottish parents, and had served in the British Army in India during World War I. In 1934, he began a sixteen-year career with The Sun of New York, later known as The New York World-Telegram and Sun. A resident of Brooklyn Heights, he rose from correspondent to become managing editor of The Sun’s European Bureau after the war.

During World War II, Gault MacGowan covered the Battle of Britain and the disastrous Raid on Dieppe, along the French coast, by the Canadian Army and British commandos (in which he wrote about a German dive bomber strafing and bomb dropping around his ship). While reporting in December 1942 from North Africa, particularly in and around Medjez-El-Bab, in a valley on the road toward German-held Tunis, he fearlessly rode his jeep under shellfire. He was described by one fellow war correspondents as “a blazing ball of fire” who always was on the front line “crawling among the troops under fire, with his pencil and paper, asking them if by any chance they come from New York, and if so, how they’re doing.” Ernie Pyle called him the “oldest” correspondent there. After the defeat of Rommel in Africa, MacGowan travelled to Italy. On June 6, 1944, he covered the D-Day Invasion of Normandy and then he was attached to General Omar Bradley’s forces. He risked his life very often to get a news story. On August 15, 1944, while venturing unarmed in a jeep to the town of Chalons-sur-Marne, near Chartres, France, well beyond the American First Army’s front lines, he and two journalists were attacked by two German Armored Cars. After a machine gun opened up on them, their jeep struck a hedge and was up-ended. William Makin, a British war correspondent (and a close friend of MacGowan,) who was in the back seat, was shot, and had a fatal stomach wound. He was captured. The other war correspondent, Paul Holt, the driver, played dead on the ground while the German soldiers searched the vicinity. With the help of a French soldier, he soon was able to escape. MacGowan was captured. He spent nine days in captivity, and managed to escape by jumping out of a prisoner-of-war train in the middle of the night, with German guards firing at him. He eluded his captors, and the French Resistance found him and saved him. News of his capture, escape and rescue appeared in daily newspapers in London, New York, and elsewhere around the world. In April and in May, 1945 he gave The Sun an eyewitness account of the liberation of the Buchenwald and Dachau death camps. He accompanied General Patton’s forces and visited the scene of Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest at Berchtesgaden at the war’s end. He was awarded 19 medals during his service as an accredited U.S. Army War Correspondent.

As a war correspondent in World War II, and even as a reporter working for The Sun, back in New York, Gault MacGowan had high integrity and a professional commitment to honoring the facts. He always followed the news story wherever it led him, despite the danger. When he and his fellow American war correspondents sailed to Algeria, North Africa in 1942, he was in very good and highly esteemed company. On board were his colleagues, Ernie Pyle, Bill Lang of Time and Life, Rob Mueller of Newsweek, Olie Stewart of The Baltimore Afro American, Sergeant Bob Neville, correspondent of the papers Yank and Stars and Stripes. But two censors were also onboard, Lieutenants Henry Mayer and Cortland Gillett. Following the British and American tradition of honoring free speech, this generation of print journalists as war correspondents were courageously dedicated to telling the truth under any circumstances, regardless of the result, come hell or high water.

N.B. Speaking about the journalistic experience of his fellow war correspondents aboard that ship, Ernie Pyle said, “Neville was probable the most experienced and travelled of all of us – he speaks three languages, was foreign news editor of Time for three years, has worked for The Herald-Tribune and PM, was in Spain for that war, in Poland for that one, and in Cairo for the first Wavell push, and in India and China and Australia.”

REFERENCES

Ernie Pyle, “Blackout Fails to Impress Men of Ship,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 December 1942, p. 42

A review of Gault MacGowan’s life as a war correspondent in World War II

Alice Hughes, Soldier-Dad Hears about this Baby’s Birth,” The Akron-Beacon Journal, Akron Ohio, 30 May 1943, p. 14

“Correspondent is German Prisoner,” Associated Press (AP), London, 15 Aug 1944

“MacGowan’s Escape a Mystery,” North American Newspaper Alliance, New York, 06 Sep 1944

INEZ ROBB, AUTHOR OF

“PRETTY WAAF GIRLS TAKE CARE OF A LADY-KILLER-ROMEO (BALLOON BARRAGE)”

INEZ ROBB (on the right) interviewing British women, members of the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), at an anti-aircraft site to defend London, January 12, 1942 (photo: International News Service)

Inez Robb (1901-1979) was born in Boise, Idaho and she was dubbed “Newspaperdom’s Number One Female Reporter.” During her long 40-year career, this award-winning American Journalist met over 10,000 deadlines. She always carried her own typewriter and reported on kings, royalty and presidents, athletes and world events. She reported for the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate and the United Features newspaper syndicate.

In later 1941, one week before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, as “star feature writer for International News Service,” she travelled to England where she wrote a series of articles on the British Women’s Armed Services. These articles were read alike by the American people and members of the U.S. Congress, and they served to inspire the law that created of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAACs) in the U.S.A.

In January 1942, in response to the British government’s announcement that women would be conscripted into military service, Inez Robb wrote:

“The mother of parliaments through its unprecedented conscription of women, has forever answered in the affirmative the feminist battle cry “are women people?”

“England has learned by more bitter experience than any nation that women are people who contribute blood, sweat and toil and not merely tears to the national effort required to wage war. In the second World War, English women work at their war jobs as grimly and as gallantly as Englishmen.

“England has begun to call up the first classes of women subject to compulsory service under the nation’s powers for mobilization of the population.

“England becomes the first nation in the history of the world to adopt general conscription for women. Now such conscription is limited to women between 20 and 30. The millions of women in her factories, industry, post offices, railroads, land army, civilian defense and actual military service, England thus plans to add thousands more.

“In the England of 1942, women are denied but one prerogative: That of bearing arms.”

When the Germans broke through the American lines at the Kasserine Pass in Tunisia, North Africa in February 1943, she was there. “I had many reasons for wanting to see the war,” she later said, “The strongest one was that it was the biggest story of all. And then I felt that an American woman should observe what war meant. No woman in my memory had the faintest conception of its effects, although thousands of women in other countries had suffered from it.”

In her travels she collected recipes from all over the world. She recalled, “My most distinguished contribution, perhaps, to World War II was to teach some unsung G.I. cook in Tunisia how to improve the Army’s canned beef stew.”

Inez Robb was such a competent, reliable news reporter and influential columnist that many of her colleagues believed she made it much easier for women to get jobs in newsrooms throughout the country.

REFERENCES

Inez Robb, “Women Do Man-Sized Jobs to Help in War Effort,” Star-Tribune, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 12 January 1942, p. 11

“Inez Robb Ends Her Long Career in Journalism – Special to the Honolulu Advertiser,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Honolulu, Hawaii, 09 Feb 1969, p. 50

*****

BKM 11/12/2020