THE BATTLE OF NAUSET BEACH, CAPE COD, MASSACHUSSETTS, USA

By Bruce K. McWhirk

FRIDAY, JULY 19, 1918:

B-12 BLIMP GOES MISSING

THE U.S. NAVY’S B-12 BLIMP PATROLS FROM CHATHAM, CAPE COD LOOKING FOR GERMAN U-BOATS

The following article appeared in the Aircraft Journal in 1919. It describes the disappearance from Naval Air Station (NAS) Chatham’s of its B-class Blimp, B-12 while on anti-submarine patrol over Atlantic waters and the survival of its crew:

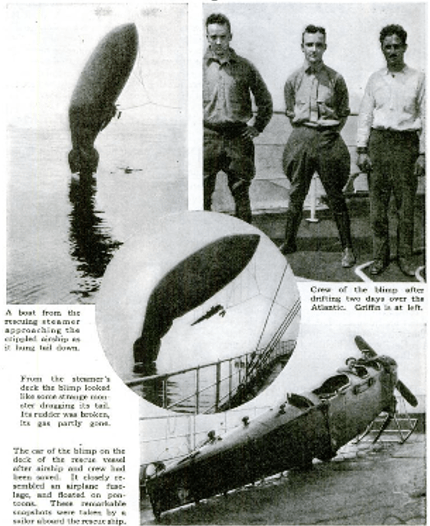

“An unusual story of hardships, daring and the miraculous escape from death during the war was brought to light for the first time when naval officers made public an account of the adventures of the crew of the Navy airship B-12, which was given up for lost by the department in July, 1918, after drifting around at sea for more than two days, during which time the crew had practically nothing to eat and ran short of drinking water. The dirigible finally was forced to descend on the surface of the sea, and the crew was rescued by the Swedish ship Skagern.

“B-12, with Ensign W.B. Griffin, as commanding officer and pilot, Ensign W.C. Briscoe as assistant pilot, and Machinist’s Mate E.A. Upton as mechanic, was ordered to leave Chatham, Mass. early July 19 on a patrolling expedition. German submarines were operating off the Atlantic Coast, and the dirigible was well loaded with bombs when it left the air station. Scanty food supplies were carried, as Ensign Griffin expected to return to Chatham that night. The radio equipment had only been partly installed and could not be used to send or receive messages.

“The B-12 patrolled to the north along the coast and sighted a transport about 3.30 p.m. Ensign Griffin headed toward the vessel, intending to escort it toward port, when the heel brace on the rudder was carried away, making it impossible to steer the craft. High winds were prevailing at the time, and the B-12 was forced to cruise around in a great circle while the crew attempted to attract the attention of several ships and two seaplanes then in sight. No attention was paid to repeated signals and finally Ensign Griffin ordered the motors cut off in order to save the gasoline for ballast.

“The B-12 at that time was about 200 feet in the air, and was virtually a free balloon. Darkness was coming on, and the gas bag was drifting northward at a speed of about twenty-five miles an hour, with an increasing wind behind it. A sea anchor was rigged up and an effort made to retard the dirigible’s progress by dragging it in the sea. After a few moments, however, the towing cable parted, and the northward progress was resumed at an increased speed.

“About 9:30 o’clock that night a ship was sighted and nine rockets were fired from a patrol. The vessel apparently saw the signals, and directed its course toward B-12, only to turn away in a few moments and leave the helpless gas bag to the mercy of the wind. About that time the pipe line leading to the emergency fuel tank broke, and before the leak was discovered all the oil was lost, causing a considerable decrease in ballast. The B-12 began to rise and ascended steadily until an altitude of 3,000 feet was reached.

“All night the dirigible continued its wild dash northward, the crew meantime consuming the small amount of food aboard. Ensign Griffin had no idea of his whereabouts.

“Early on the morning of the second day the gas bag buckled and the horizontal fin dropped to a vertical position. Throughout the day the dirigible alternatively dropped until perilously near the sea and ascended to altitudes of more than 2,500 feet. Every available article was thrown overboard during these variations in altitude to keep the airship from plunging into the ocean. Not a vessel was sighted that day or that night. The crew meantime was beginning to suffer from hunger.

“On the morning of the third day of the involuntary cruise, the sun shone brightly, and, as the gas in the bag expanded rapidly, the B-12 started to rise. Ensign Griffin, after a conference with the other members of the crew, decided to bring the B-12 to the surface and take a chance of being picked up. To avoid the risk of ascending to a high altitude with only a small amount of ballast aboard, gasoline, water, sand, bombs, bomb- launching gear, batteries, and the radio outfit parts were dumped overboard and B-12 brought to the surface safely.

“Soon after the descent a ship was sighted and it directed its course toward the dirigible, the crew of which meanwhile was having great difficulty in keeping clear of the water. The vessel proved to be the Swedish steamer Skagern, bound for Halifax. A small boat was put over the side, and the crew of the B-12 was take-off. Then, as the increasing heat from the sun caused the gas to expand, the dirigible rose a few feet above the surface, and was pulled over to the Skagern, the rip cord pulled, the B-12 was salvaged without much damage more than 300 miles from its home station.”

“Miraculous Escape of the Navy Blimp B-12”, Aircraft Journal, vol. 5, No. 4, Gardner-Moffat, New York, July 26, 1919, p.12

SUNDAY MORNING, JULY 21, 1918:

ADRIFT FOR THREE DAYS, ENSIGN W.B. GRIFFIN, U.S.N. AND HIS CREW ABOARD B-12 DIRIGIBLE ARE RESCUED BY A SWEDISH STEAMER – THEIR B-CLASS BLIMP IS RECOVERED

MIRACULOUS RESCUE: The crippled B-12’s crew stand for a photo: Ensign Walter H. Griffin, U.S.N., (left). These remarkable snapshots were taken by a crewman aboard the rescuing Swedish steamship, S.S. Skagern, (8,800-ton) owned by Rederiaktie-bolaget Transatlantic (Transatlantic Group), Gothenburg, Sweden. The B-12 is seen floating in the water; the control car was placed on the ship’s deck. (Source: “Adrift Over the Sea in a Crippled Blimp,” Popular Science, vol. 115, no. 3, Popular Science Publications, New York, September, 1929, p. 63)

SUNDAY MORNING, JULY 21, 1918, 10:30 A.M.:

A GERMAN U-BOAT ATTACKS THE U.S.A.

SUMMER BEACHGOERS AT NAUSET HEIGHTS BLUFF AND COTTAGES, ORLEANS, CAPE COD, MASSACHUSETTS, U.S.A. (postcard provided by Roberta Hulburt, Orleans Historical Society)

THE BATTLE OF NAUSET BEACH, CAPE COD, MASSACHUSETTS, U.S.A.

The Battle of Nauset Beach marked the only raid mounted by the Central Powers against the Continental United States during World War 1. It was the first time the Continental United States was attacked by a foreign power since the Siege of Fort Texas in 1846, and the first time the coastal United States was attacked by a foreign power since 1812.

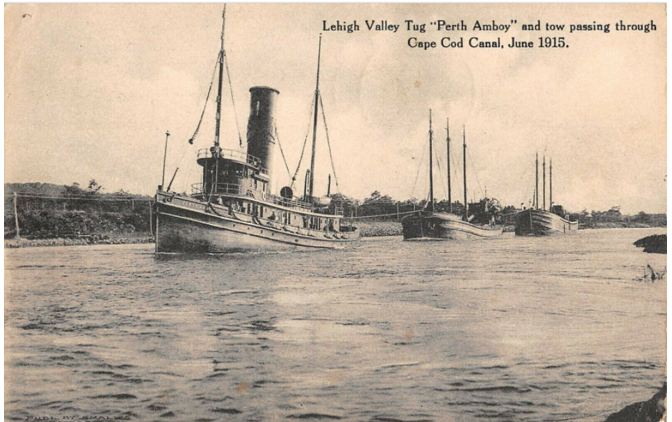

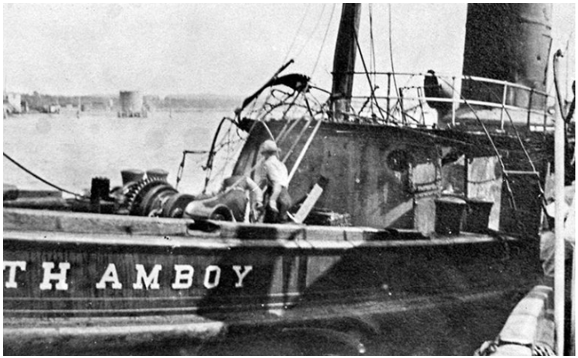

On Sunday morning, at about 10:30 A.M., on July 21, 1918, during a summer heat wave, astonished beachgoers at the crowded Nauset Beach in the Town of Orleans on Cape Cod, Massachusetts saw the German U-boat, SM-U156, suddenly emerge from a thick foggy mist four miles offshore. The U-boat suddenly began relentlessly firing its big deck gun on an unarmed tugboat, Perth Amboy, and its four barges in tow, as they steamed leisurely through the calm sea. Three of the barges were empty and the fourth barge carried a load of quarried stone. The tug’s captain, J.P. Tapley, shouted a warning to his crew of seven as he saw the deck gun begin firing and saw what he thought was a “torpedo” shoot by. The U-boat gunners fired close of 150 rounds from their deck gun and hit and heavily damaged the tug and sank all of the barges. The tug was set ablaze and several crewmen aboard the tug and the barges were injured.

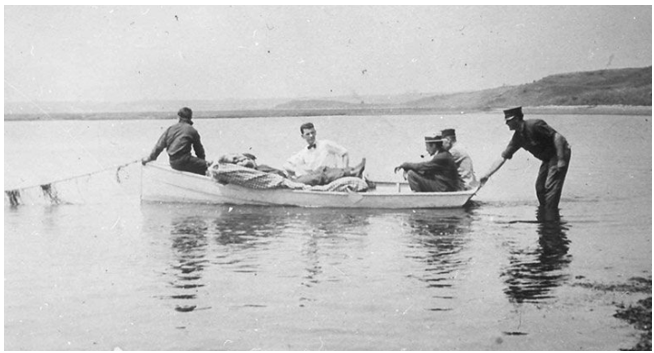

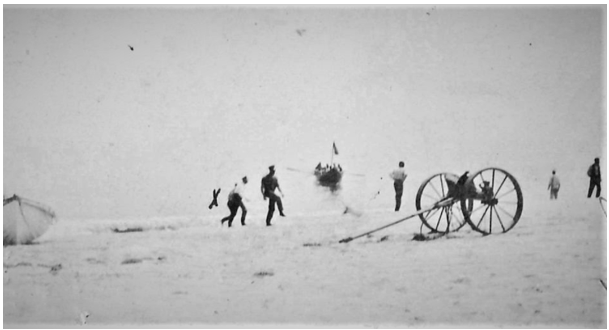

Surfmen from the nearby Coast Guard Station No. 40 in Orleans, under the leadership of Robert F. Pierce (Surfman No. 1), quickly responded to calls for help. Being skilled in the art of handling small boats, they rescued all the civilians from the burning and sinking vessels.

RESCUED: The unarmed tug Perth Amboy’s crewmen make it ashore at Nauset Beach while German U-boat’s crewmen wildly fire their deck gun at the tugboat and the four schooner barges. (photo: Orleans Historical Society)

While the U-boat was firing its salvoes, 41 people in all were saved, including three women and five children. As the surfmen rowed in their lifeboat toward Perth Amboy, their caps flew off due to the force of the exploding shells. Captain Ainsleigh, master of the barge Lansford, claimed that the U-boat had fired three torpedoes at his barge, but none had hit their mark. Many of the summer residents ran to their nearby cottages to seek safety after they realized that the German deck gun crew, being extremely poor marksmen, were firing their gun wildly and hitting points on land.

According to the official account of the attack, The War Diary of the First Navy District in Boston, “The shooting of the enemy was amazingly bad… For more than an hour the blazing tug and the drifting barges were under fire before the enemy succeeded in getting enough shots to sink them… the submarine crept nearer until her range was only a few hundred yards… This at length proved sufficient and the barges disappeared beneath the surface one by one until the stern of the Lansford (second barge in the row) was visible… Shrapnel bursting over the Lansford, second in the tow, struck down Charles Ainsleigh, master of the barge.”

Captain Marsi Schuill, master of the fishing smack, Rosie, out of Provincetown, witnessed the attack on the tug and barges and his boat with a crew of seven was attacked at the same time by the same submarine. Describing the U-boat attack, he said,

“She looked like a big whale, with the water sparkling in the sunlight as it rolled off her sides. Then we saw the flash of a gun on the U-boat and saw the shell strike the pilot house of the tug. A few minutes later we saw fire break out and the crew running toward the stem. Then the U-boat turned her attention to the barges. We then saw one of the deck guns on the U-boat swung around toward us and there was a flash. A shell came skipping along the water. I ordered full speed ahead, and the Rosie jumped ahead through the brine, making us feel a little bit more comfortable. The Germans must have fired as many as five shots at us, the nearest coming within 10 feet of our stem but we were traveling pretty fast and when the submarine crew saw their shots were falling short, they gave up. “

SHELL SHOCKED: More crewman of Perth Amboy being brought ashore in a lifeboat during the U-boat attack (photo: Orleans Historical Society)

During the height of the battle, James Boland, the town’s deputy sheriff, received a telephone call from a very excited woman. “The Germans are coming after us,” she shouted, “Hurry up and come down and save Orleans!”

Before the German U-boat finally ended its merciless attack and departed on the ocean’s surface, nearly 800 people, including automobile drivers who had parked their cars along the roadside on the sandhills overlooking the ocean and beach goers standing near the water’s edge, witnessed the drama. Cottagers sitting down in lawn chairs watched what some later called the “Battle of Nauset Beach.”

A group of young women were bathing in Meeting House Pond at the time. Among them was Miss Evelyn Ham of Boston. She said that one of the shots passed within a few feet of the girls’ heads and landed in the water about 500 yards away from them, but the shell only made a great splash and did not explode. Strangely, the girls were not frightened at all and later joked about the incident.

Confidently expecting a German invasion from the submarine, Maj. Herbert L. Harris telephoned local members of the State Guard and ordered them to quickly assemble at the village center.

One U-boat shell, officially verified by crater analysis, had landed 100 yards in the beach of Nauset Harbor, making the U-boat raid the first and only time the U.S. mainland was attacked during World War I.

TUG PERTH AMBOY TOWING SCHOONER BARGES (contemporary postcard)

Fired upon by the German U-boat, the upper part of Tug Perth Amboy was riddled with shells fired from the U-boat and badly burned, but there was almost no damage below the waterline, and its engine remained in good working order.

AN ACT OF COURAGE

Jack Ainsleigh, the 11-year old son of Lansford’s skipper, Captain Charles Ainsleigh, stood on the barge’s deck waving the American flag during the German U-boat attack. Amid the smoke, fire and shelling, his father, already slightly wounded in both forearms by shrapnel, told the boy to get into the lifeboat. At the time the boy was getting his brother’s .22 caliber rifle to return shots at the U-boat. (photo: William P. Quinn)

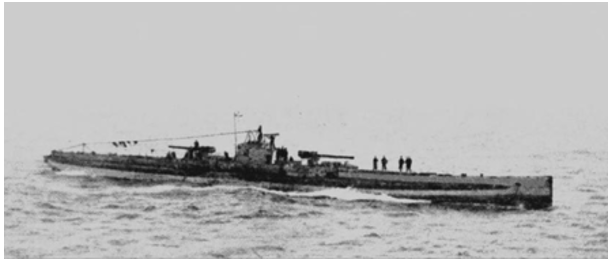

SEA RAIDER: THE GERMAN U-BOAT: SM U-156

SM U-156 – one of the German Navy’s largest U-boats, SM-U-151 type U-boat, that under took a terror campaign against ships in North American waters. (photo: DND U156-003)

The SM U-156 sank 45 ships during World War 1. Rear Admiral William S. Sims U.S.N. claimed, and U.S. Navy archeologists decades later confirmed, that the 500-foot warship U.S.S. San Diego (ACR-6) was sunk off of Fire Island, Long Island and near New York Harbor by a mine laid by SM-156.

Kapitänleutnant Richard Feldt, commander of German U-boat SM-U156 (photo: www.u-boat.net)

After the U-boat attack at Orleans, SM-U156’s commander, Kapitänleutnant Richard Feldt, was credited with sinking the tug Perth Amboy (435 tons); the barge 703 (934) tons; the barge 740 (680 tons: the barge 766 (527 tons) and the barge Lansford (830 tons).

SM U-156 was built at the Atlas Werke in Bremen and was commissioned in August 22, 1917 for the Imperial German Navy. Being one of the largest and most technologically advanced designs of the Kaiserliche Marine’s submarines, SM U-156 was part of the U-Kruezer Flottilla based in Kiel, Germany.

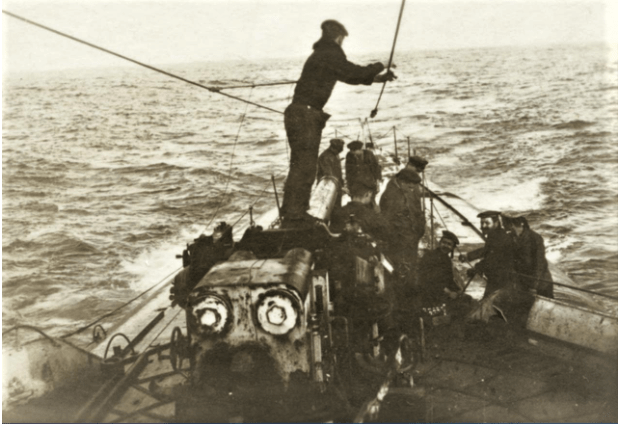

A view from SM U-156’s conning tower showing the U-boat’s forward placed 5.9-inch deck gun and its crew. (photo: Lowell Thomas Papers, James A. Cannavino Library, Archives and Special Collections, Marist College, U.S.A.)

This long-range cruiser U-boat was designed like the commercial cargo carrying U-boat Deutschland to sail great distances across the Atlantic Ocean. SM U-156 carried a compliment of 6 officers, 77 enlisted. This U-boat’s armaments included two 5.9-inch deck guns, 18 torpedoes and shaped mines discharged through its torpedo tubes.

During World War 1 German U-boats sank more than 100 vessels in American waters.

COUNTER ATTACK!

Lieut. Phillip B. Eaton, USN, Commander at NAS Chatham, (center) and his fellow officers (photo: U.S. Coast Guard).

NAS CHATHAM RESPONDS TO THE U-BOAT ATTACK

Seven miles south of Orleans, at Chatham Naval Air Station, Executive Officer Lieutenant j.g. Elijah Williams heard the rumble of distant naval gunfire. Half of the station’s pilots were out in two seaplanes searching for the station’s missing blimp, B-12. Most of the ground personnel were at Provincetown, (the town situated at the end of the Cape,) for a leisurely, Sunday morning baseball game against a minesweeper’s crew. Then his signalman received an urgent telephone call from Station chief Robert F. Pierce at Coast Guard Station No. 40 in Orleans. This message alert confirmed what Williams most feared: a U-boat was attacking nearby American vessels. The time was 10:40 AM.

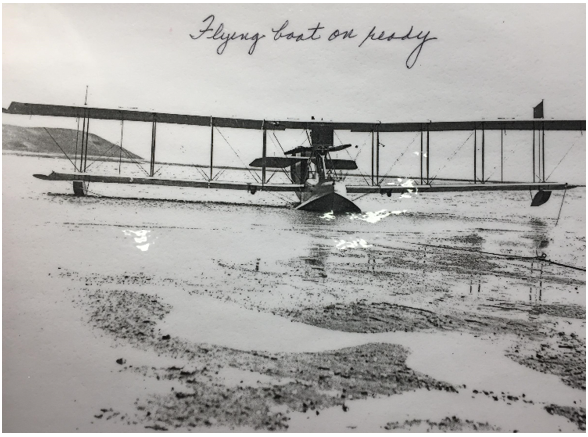

A Curtiss HS-1L (photo: Chatham Historical Society)

Lieut. Williams immediately started gathering a crew to fly the only available Curtiss HS-1L. Within minutes Ensign Eric Lingard and his crew took off in the seaplane, having a Lewis machine gun (apparently without ammunition) and a 120 lb bomb. Bearing north by northeast, Lingard and his co-pilot Ensign Edward Shields and bombardier Chief Special Mechanic Edward Howard, seated at the nose, headed for the waters off of Orleans. They were flying at the Curtiss’s top speed: 82 mph.

Reaching the area above the U-boat, Lingard nosed his plane downward for a dive-bombing run. Realizing that the Navy seaplane was overhead and rapidly descending from 800 feet above, and was making a pass over the U-boat, the German gunners on the deck scrambled for cover. Shields said. “They did not appear to see us until we were almost upon them. As we nosed down toward them, there was a great deal of commotion and hustling around on deck. They then seemed in a Hell of a hurry to get away.”

Sighting “dead on the deck,” Howard pulled the release, the bomb was hung up and did not drop. Howard motioned to Lingard to take the plane around for a second run. After circling the submarine and approaching at 400 feet, Howard tried to release the bomb again. But again, the bomb failed to release. Howard crawled out from his nose seat, and maneuvered six feet onto the plane’s lower wing. With the U-boat still in range, Lingard and Shields watched their bombardier almost fall from the wing. Regaining his balance, Howard gripped onto to a wing strut with one hand and the bomb with the other, he let the Mark IV fall on a perfect course toward the U-boat.

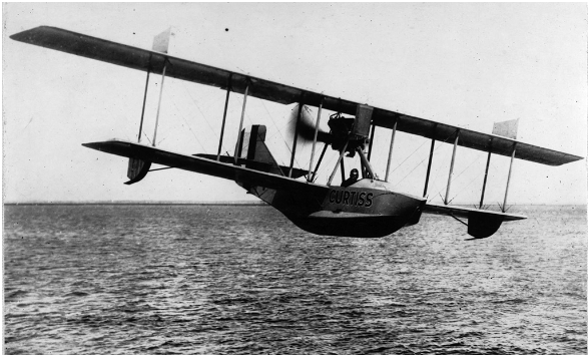

A Curtiss HS-1L in flight (photo: Cape Cod Chronicle)

When the bomb landed in the water about 40 feet from the U-boat, it failed to detonate. It bomb was a dud. As the German gunners began firing their deck gun at the approaching seaplane. Lingard quickly pulled back the joystick and pulled out the throttle, to get the seaplane to rapidly climb higher to evade the incoming high explosive rounds. The seaplanes had no wireless radio communication, so Lingard and Shields decided they would follow the U-boat from a safer distance and at higher altitude until other Navy seaplanes could arrive with live bombs.

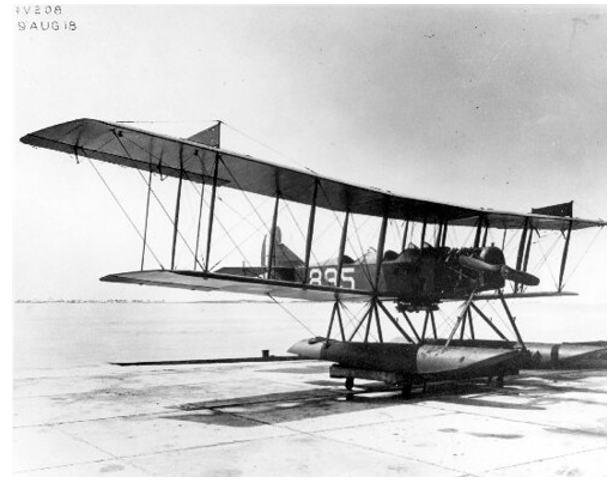

Curtiss R-9 Seaplane (photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum)

Lieut. Eaton suddenly swooped in piloting a Curtiss R-9 trainer seaplane. Flying solo, he also was acting as his own bombardier. “As I bore down upon the submarine, it fired,” he said. “I zigzagged and dove as it fired again.” The U-boat’s deck crew started going inside the submarine. “They were getting under way and scrambling down the hatch when I flew over them and dropped my bomb.” This bomb also failed to explode. It too was a dud. The time was 11:22 a.m. According to an account of the incident in the archives of the Chatham Historical Society, Lieut. Eaton, now enraged, “threw the heaviest thing he had on board—a monkey wrench—at the sub. It landed on the deck of the sub, much to the astonishment of the submarine’s crew.” After scoring this direct hit, he threw the rest of the plane’s tools and toolbox at his target, while the German sailors thumbed their noses.

Fearing that more U.S. Navy seaplanes would soon be arriving with bombs, Captain Feldt ordered the U-boat to submerge. The time was 11:30 a.m. as the U-boat dove down beneath the waves and disappeared. SM U-156 followed a zigzag southerly pattern out to sea and disappeared out of harm’s way. The Battle of Nauset Beach had lasted barely 90 minutes.

AFTERMATH OF THE U-BOAT ATTACK ON ORLEANS

Rear Admiral Spencer S. Wood, U.S.N., commander of the First Naval District, the next day at noon speaking to the press described the U-boat attack at Orleans. He said, “…the effort, from a military standpoint, was so ridiculous as to be almost a circus stunt.” He declined to comment when he was asked by a reporter why during the counterattack on the U-boat all the aerial bombs dropped by the Navy’s seaplanes had failed to detonate.

The night before, on Sunday, July 21, 1918, Harbormaster Capt. Orin C. Bartlett of Plymouth reported that at dusk he had sighted a periscope of a submarine four miles off of Plymouth in Cape Cod Bay. He said he was in a motor boat and close enough to the periscope to positively identify it as a submersible. Nonetheless, state and local authorities decided that the Port of Boston would remain open.

SM U-156 stealthily ventured north, going down-east along the New England coast. On Monday, July 22, 1918, the Gloucester fishing schooner Robert and Richard was sunk by this same U-boat off the southeastern coast of Maine.

ATTENDING TO THE INJURED CREWMEN

GETTING THE WOUNDED ASHORE: John Bogovich of the Tug Perth Amboy, who was severely wounded during the U-boat attack, appears here being brought ashore at Nauset Harbor. (photo: Orleans Historical Society)

Dr. Francis Callanan, a summer resident in Orleans, promptly treated John Bogovich, Austrian helmsman aboard the Tug Perth Amboy, after he was severely wounded in his back and both arms during the U-boat attack. Dr. Callanan treated another injured Austrian crewman, John Vitz, whose right hand was blown off, and had both men brought ashore at Nauset Harbor, and then he had them transported by train to the place of his residency, Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Getting timely medical treatment for both men saved their lives.

FOUR BARGES LOST

THE WRECK OF BARGE LANSFORD: The schooner barge Lansford (Ansleigh’s) was one of four barges attacked by the German U-boat, SM U-156. Three barges were sunk during the battle and the fourth (Lansford) was beyond repair. None of the barges were salvageable. The barges were bound from Gloucester to New York at the time of the U-boat attack.

TUG PERTH AMBOY BATTERED AND CHARRED

TUG PERTH AMBOY – A BURNED WRECK: Tug Perth Amboy and its four barrages were owned by Lehigh Valley Railroad Company of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a carrier of anthracite coal. (photo: Massachusetts Historical Society)

TUG PERTH AMBOY’S STERN AFTER THE FIRE (photo: Massachusetts Historical Society)

TUG PERTH AMBOY MADE SEAWORTHY AGAIN

EXTENSIVE REPAIR WORK: The 120-foot tug Perth Amboy, shelled by a German submarine, awaits repairs at the wharf in Vineyard Haven on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. (Photo Chris Baer)

Capt. Edward Jones Smith, a 71-year-old “Old Salt” from Vineyard Haven in charge of the wharf, received the pilot’s gold pocket watch, melted and embedded into the wheel room’s electric light fixture; it had been hanging there when the first shell struck Perth Amboy’s Pilot’s House. At the time of the U-boat attack, helmsman John Bogovich was manning the wheel and a shell fragment struck the spokes of the wheel. His right arm was broken and three pieces of steel lodged in his back. Miraculously, no heavy damage was sustained below the tug’s water line, so after topside repairs, Perth Amboy continued in service for another three decades.

ANIMALS RESCUED

Immediately after the U-boat’s melee, Walter Eldridge, a Chatham fisherman, got into his power boat and set off for the tug Perth Amboy. As he drew closer to the smoldering hulk, he heard yelps of joy coming from Jack Ainsleigh’s dog, “Rex,” that had been blown off the barge Lansford. He picked up the water-soaked dog and boarded the tug, but owing to the extreme heat of the onboard fire, he just stayed long enough to survey the damage. The only other animal on any of the vessels to be rescued was Jack Ainsleigh’s pet chicken aboard the barge Lansford.

THE FATE OF SM U-156 – IT WAS LIKELY SUNK BY A SEA MINE LAID BY THE U.S. NAVY

A U-151 TYPE SUBMARINE LYING IN PORT This photo shows SM U-155 (Deutschland) in the port of Cherbourg, France in 1919. (photo: Robert Wilden Neeser / Naval History and Heritage Command)

SM U 156 continued its reign of terror in North American waters from August to September, 1918 by sinking 29 unarmed fishing smacks, trawlers and steamers in the Gulf of Maine and off of Canada’s maritime provinces. Finally, on September 25 1918, after crossing the Atlantic Ocean and bound for its home port at Kiel Germany, SM U-156 failed to report by radio that it had cleared the Northern Barrage, the vast minefield in the North Sea between Scotland and Norway laid by the U.S. Navy.

British Naval Intelligence Room 40 had intercepted the SM U-156’s earlier message (estimating the time of the U-boat’s return to Kiel) decoded it, and sent a Royal Navy submarine to ambush it. U-156 escaped this trap by diving deep, but probably tried to clear the barrage while underwater. No subsequent radio messages from the U-boat were received. SM U-156 probably struck a sea mine in the Northern Barrage. Its entire compliment of captain and crew, totaling 77, was lost.

NAVAL AIR STATION (NAS) CHATHAM – CAPE COD, MASSACHUSETTS

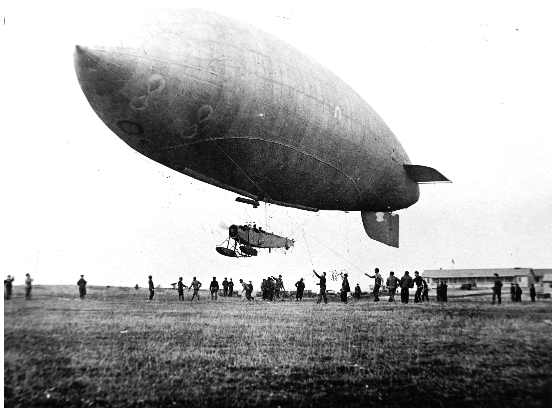

FLYING HIGH Navy B-class blimp flying over the Chatham Naval Air Station Cape Cod, in the summer of 1919. NAS Chatham provided calm waters and a safe haven for operation of seaplanes. (photo: Lieut. Arthur. D. Brewer, USNRF, naval aviator # 103, naval dirigible pilot)

U.S. Naval Air Station (NAS) Chatham was commissioned on January 6, 1918. The 36-acre station in North Chatham was located at Nickerson Neck along the protected waters of Pleasant Bay at the southeastern elbow of Cape Cod. Ground broke to build the air station on August 29, 1917, and it took five months to build. Once opened, the station’s mission was to patrol for German U-boats using its three seaplanes and B-12 blimp.

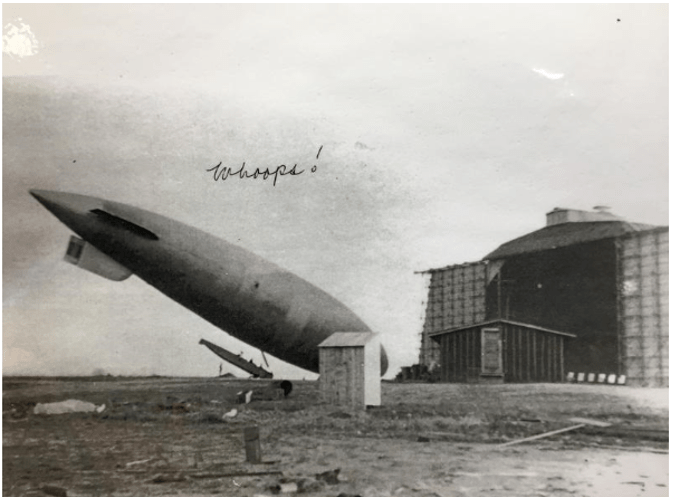

IN THE HANGER B-12 blimp inside its hanger at NAS Chatham (photo: Atwood House Museum, Chatham, MA)

This B-class blimp was housed in a gigantic wooden hangar measuring 252-feet long, 125-feet wide, and 75-feet high.

The Allies’ greatest challenge since World War 1 was protecting the increasing traffic in the shipping lanes from lurking German U-boats; in the waters off the northeast coast of the United States, U.S. Navy-led convoys of American merchant ships carried ammunition, food, and supplies from New York and Boston and ports along the eastern seaboard of the United States to the Allies in Europe. The station’s specific mission for its coastal patrolling airship and seaplanes operating over in Massachusetts waters was to protect these commercial vessels from U-boat attack between Cape Cod to Cape Ann.

Another critically important mission for NAS Chatham was the defense of the trans-Atlantic cable that ran for more than 3,000 nautical miles from Orleans to Brest, France. This underwater cable transmitted most of the military communications between Washington, D.C. and General John J. Pershing, U.S. Army, commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France during World War 1. The German Imperial Navy wanted to severe this strategic communications line.

Naval Air Station (NAS) Chatham, Cape Cod, remained in operation as a U.S. Navy airfield from 1917 to 1922.

POSTCRIPT: B-12 LOST AT SEA, JANUARY 14, 1919

B-12 MAKES A HARD LANDING (photo: Chatham Historical Society)

B-12 never participated in the Battle of Nauset Beach.

B-12 TAKING OFF AT NAS CHATHAM, CIRCA SEPTEMBER, 1918 (contemporary postcard)

The following news item appeared in the magazine Flying in 1919:

“Chatham Mass., January 14 – Four men from the naval aviation camp saved themselves from being carried out to sea in a disabled ‘blimp’ balloon today by jumping into the water a short distance from shore. They were followed by seaplanes, one of which picked them up and brought them back to camp. Lieut. Walter H. Griffin, officer in charge of the party, was slightly injured.

“The balloon rose to a considerable height when relieved of the weight of its passengers. When last seen it was about thirty miles off Chatham, travelling northeasterly at twenty miles an hour.”

Calendar of Events, Flying, vol. 8, no. 1, Flying Association, New York, February, 1919, p. 76

EXTRACT: War Diary of the First Naval District.

The following extract is from The War Diary of the First Navy District in Boston, that appeared in The Seabound Coast: The Official History of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1839- 1939, vol. 1, William Johnston, William G.P. Rawling, Richard H. Gimblett, and John MacFarlane, Dunham Press, Ontario, 2010, p. 661-662:

War Diary of the First Naval District. —

“Capt. J. P. Tapley, of the Perth Amboy, who was in his cabin at the time, ran out on the deck just as the submarine loomed out of the fog bank, her deck gun flashing out its storm of steel. The bombardment set the tug on fire, and the German then turned his attention to the helpless barges.

CAPT. CHARLES AINSLEIGH OF THE SCHOONER BARGE LANDFORD WITH HIS FAMILY

(L to R) Mrs. Ainsleigh, Jack R. Ainsleigh, Charles D. Ainsleigh, Capt. Charles Ainsleigh (photo: Boston Post, July 22, 1918, p.6)

“Shrapnel bursting over the Lansford, second in the tow, struck down Charles Ainsleigh, master of the barge. The shooting of the enemy was amazingly bad. For more than an hour the blazing tug and the drifting barges were under fire before the enemy succeeded in getting enough shots to sink them. In the meantime, the submarine crept nearer until her range was only a few hundred yards. This at length proved sufficient, and the barges disappeared beneath the surface one by one until only the stern of the Lansford was visible. The tug was a burning hulk.

In this instance the submarine crew removed nothing from their victim other than the flag and the ship’s papers.

____________

A thrilling story of how the Boston fishing boat Rose, on a seining trip, was fired upon several times by a German submarine off Orleans, Cape Cod, Mass., being missed by only 10 feet, together with her flight for safety, was told to-night upon her arrival in Provincetown by Capt. Marsi Schuill. The captain and his crew of seven witnessed the attack on the tug Perth Amboy and the four barges. The captain said:

“We were about 5 miles off Orleans at 10.30 this morning, and the sea was as calm as a mirror. About 2 miles ahead of us the tug and her tow of four barges was steaming lazily along. Suddenly we heard the report of a big gun. We looked toward the tug and her tow and were startled to see a submarine break water.

SURFMEN FROM COAST GUARD STATION NO. 40 RACE TO HELP THE APPROACHING LIFEBOAT FILLED WITH DISTRESSED CREWMEN FROM ONE OF THE VESSELS ATTACKED BY THE U-BOAT The carriage in the foreground hauled a lifeboat to Nauset beach. (photo: Orleans Historical Society)

“She looked like a big whale, with the water sparkling in the sunlight as it rolled off her sides. Then we saw the flash of a gun on the U-boat and saw the shell strike the pilot house of the tug. A few minutes later we saw fire break out and the crew running toward the stem. Then the U-boat turned her attention to the barges. We then saw one of the deck guns on the U-boat swimming around toward us and there was a flash. A shell came skipping along the water. I ordered full speed ahead, and the Rosie jumped ahead through the brine, making us feel a little bit more comfortable. The Germans must have fired as many as five shots at us, the nearest coming within 10 feet of our stem but we were traveling pretty fast and when the submarine crew saw their shots were falling short, they gave up. A few minutes later we saw a naval patrol boat tearing toward the submarine, but we didn’t stop.”

REFERENCES

PRIMARY SOURCES

Surfman Reuben Hopkins (an oral history) on his participation in the Battle of Nauset Beach (Orleans Historical Society, OHS 1968 presentation: “Attack on Orleans!,” July 21, 1918) https://www.orleanshistoricalsociety.org/attack-on-orleans-1918

“Bombs Dropped on U-Boat Near Orleans Fail to Explode,” The Boston Globe, Boston, MA, July 22, 1918, pp. 1, 2

“Shelled by Submarine Off Coast Cape Cod”, The Boston Post, Boston, MA, July 22, 1918, pp. 1- 2 and 6

“U-boat Sinks Three Barges Off of Cape Cod; Tug and Fourth Barge Set on Fire; No Lives on Victims Ships Lost,” The Fall River Daily Globe, Fall River, MA, July 22, 1918, pp. 1, 3

“Schooner Sunk by German Sub,” The Boston Globe, August 4, 1918

“Avion”, The Way to Fly: An Introduction to Flight for Beginners, J.B. Lippincott, London, 1919, p. 62

Photo: Jack Ainsleigh, January 21, 1919 – “Boy’s Activities – War Work – Jack Ainsleigh, Boy Scout, and son of Capt. Ainsleigh of the barge, Lansford, and his pet chicken, the only animal survivor of the torpedoed barge”, National Archive – https://nara.getarchive.net/media/boys-activities-war-work-jack-ainsleigh-boy-scout-and-son-of-capt-ainsleigh-e82455?zoom=true

German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada 1920, publication No. 1, NAVY DEPARTMENT – OFFICE OF NAVAL RECORDS AND LIBRARY, HISTORICAL SECTION, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1920, pp. 55-56

SECONDARY SOURCES

Christ Baer, “This Was Then: The Perth Amboy – When the Germans took aim at a tugboat,“, Martha’s Vineyard Times, July 18, 2019

Paul N. Hodos, The Kaiser’s Lost Kruezer – A History of U-156 and Germany’s Long-Range Submarine Campaign Against North America, McFarland & Company, Jefferson, North Carolina, 2018

Jake Klim, “How a Tiny Cape Cod Town Survived World War I’s Only Attack on American Soil”, Smithsonian Magazine, July 19, 1918 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-tiny-cape-cod-town-survived-world-war-is-only-attack-american-soil-180969691/

Jake Klim, Cape Cod Chaos, www.historynet.com

Jake Klim, Attack on Orleans: The World War I Submarine Raid on Cape Cod, The History Press, Charleston SC, 2014

Christina Larson, “Scientists scour WWI shipwreck to solve military mystery” Associated Press, December 13, 2018 https://apnews.com/article/8c85bfa0776d4cad8bc329da08beba51

Deborah Lawless, “Chatham Air Station Played Role In Only WWI Attack On U.S.”, Cape Cod Chronicle, 18 July 2018 https://capecodchronicle.com/en/5329/chatham/3283/Chatham-Air-Station-Played-Role-In-Only-WWI-Attack-On-US.htm

Daniel Lombardo, Images of America – Orleans, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, SC, 2001

Brian Morris, Tracking U-Boats from the Skies Above North Chatham, January 29, 2018

James R. Shock, U.S. Navy Airships 1915-1962, 2001, Atlantis Productions, Edgewater Florida, p. 21

Rear Admiral William Sowden Sims, U.S.N., The Victory at Sea, Doubleday, Page & Co,, New York, 1921, p. 319

Lawrence Sondhaus, German Submarine Warfare in World War I: The Onset of Total War at Sea, Rowman and Littlefield, London, 2017, p.98

July 21, 1918 “German U-boat Attacks Cape Cod,” massmoments.org https://www.massmoments.org/moment-details/german-u-boat-attacks-cape-cod.html

NAVAL ARTILLERY Captain Richard Feldt’s U-156 had two 5.9-inch deck guns, placed fore and aft, identical to those appearing in this photo of its sister submarine, SM U-155 (Deutschland). (photo U-Kreuzer SM U-155 on display at St. Katherine docks, London, England in December 1918 – Imperial War Museum)